GOOD-BYE DANNY GROSSMAN

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

The American-born, Toronto-based choreographer has died at age 80. I am sorry to learn of his passing. I covered his work as a dance critic for decades. He called me over a year ago to ask if he could include my writing about him in an archive he was developing , and of course I said yes. It would be a honour to have my name in any way associated with his. Among that pile is this piece, written in 2000 for the Globe and Mail; it is fitting to reproduce it here as it about Danny preparing for death. He called his piece Transcendence as death wouldn’t be the end of him. It would launch him into new immortal territory. His works will live on. They were powerful statements about our times. I am glad to have known him, even if mostly from a chair in the dark in a theatre.

Danny Grossman is in a chair in his Toronto studio. His hands are flailing. His body is tipping east and west, as if a gale were blowing at his sails. And his mouth, well, it never stops moving through almost an hour of talk about a life spent in dance. Even when sitting, the guy is moving. And moving still.

Tonight, the big daddy of Toronto modern dance performs a solo he created for himself at the ripe old age of 58.

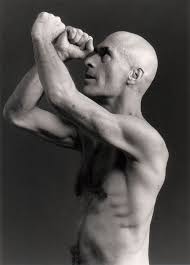

Transcendence, a 10-minute piece that he performs nearly naked to a score by acclaimed Canadian composer Ann Southam, is about Grossman now — an older man facing the inevitability of his own death. It is only the fourth solo he has crafted for himself out of a career that has included 36 pieces created for his Toronto-based Danny Grossman Dance Company.

But as the title suggests, there is no finality in the going.

Grossman is a firm believer in altered states. He has to be. Dance for him is not about steps; it’s about transformative power.

“People are transformed by dance, some by just doing it, others by watching,” Grossman said, his voice still reflecting a bit of surfer twang, despite living in Canada for most of his adult life.

He is dressed in what can only be described as artist casual — jeans, flat shoes and a rainbow-coloured beanie that covers a head shaved bald.

Until recently, he had had long, shoulder-length hair, sort of a bohemian trademark. But he cut it all off in a fit of rage over ongoing government cuts to his 12-member troupe. The recent snip was just over 9 per cent. Still, it was enough to send him over the proverbial edge, which was how the solo, debuting at Premiere Dance Theatre as part of his company’s annual, week-long run there, was born.

“It’s not ended up being about what provoked it,” Grossman said. “It’s ended up being more special.”

Still, he can’t not talk about his anger. He is fulsome about it. He describes himself going to the gym, lifting weights over his head and seeing himself as a Christ figure, nailed to the cross. Then he imagined himself as a prisoner on death row, eyeing the electric chair, knowing that this was it — the big smoke.

“But slowly I started to see that I didn’t need to be the victim,” Grossman offered almost gleefully. “I started to create a dance for myself that ended up not being about feeling degraded at all, but uplifted. Strange.”

Strange, maybe. But also inevitable. Grossman is a born dancer, the kind of person who, growing up in sunny California during the dark times of Deep South lynchings and McCarthy-era witch-hunts, was always dancing. (His late father, a civil-liberties lawyer who represented blacks at a time when it was dangerous to do so, was blacklisted.)

He had parties, lots of them, themed to showcase the latest dances of the day. People came from far and wide just to dance until the sun came up, on the carpet of his parent’s middle-class home. Those sock hops hold much in common with today’s raves, attracting, as they did, dancers of every stripe to boogie into a new day. Both are about reaching levels of transcendence.

Of course, it’s not the first time dance has been thus used. It’s long been a medium for achieving transcendence over our mundane lives. Even today, religious sects around the world use dance to experience ecstasy, among them the Whirling Dervishes of Turkey and the Mousseye of Chad. Even those who perform dance for a living usually do so because the movement transports them to another plane of being. (It’s not for the money!) The young hero in the newly released film Billy Elliot describes it as “like electricity.” Dancing uplifts and transforms.

Grossman knows that as sure as he knows that his body is aging and probably shouldn’t be letting him take to the stage any more. “But that’s the miracle of dancing,” he exclaimed. “It transforms while you are doing it.”

In fact, Grossman has such a bad hip that several doctors have told him he needs to have it replaced. The problem is so severe that he experiences agony when walking across the street. “But I start dancing and I’m like a kid again! I feel no pain. Look, look, I’ve dropped my crutches!”

He lets out a mock holy-roller whoop and says “Amen.”

But all jokes aside (and there are a few tossed about this easy afternoon), Grossman is deeply reflective about his art. There is perhaps no one as analytical and scholarly about his own output. It is almost like listening to Northrop Frye discussing Blake.

“In Visionary Realm [his work of 1996], I brought the shaman back to the womb, or rather back to the earth. He journeys back, and is confronted by his own androgyny or fear of the transformative self,” he said. “Some of it is reflected as intuitive forces. There is the deer who is his guide to the other world, and the wolf represents the death figure. He adopts wings, and journeys to the spiritual world. Well, you can see, I have always been interested in the same theme. All my work has been about altered states.”

And that’s just one work out of about 20 that he mentions.

But it is not pretention on his part, or grandstanding. He does not create consciously, but emotionally. Meaning, in his case, follows movement. Looking back now, with the eyes of the mature artist, he is deeply fascinated by the shape and pull of his own work, as if he were an outsider looking in.

Being privy to it all is rewarding and informative: He is the repository of his own dance history. He knows all too well the ephemerality of dance. Funding cutbacks only remind him, even more, of his art form’s fragility. “If we’re erasing our own history while we’re making it,” Grossman asked, “then why do it? Why make it more ephemeral than it is?”

It’s a rhetorical question, because Grossman won’t quit now. From his position as a senior player in the local arts scene, he can look at his career and see the thematic arc, the big message. And all is well. The career is describing a path that has led him on a journey of, well, transcendence.

“So in a way, I’m not just coming to terms with my own death,” he said. “I am freeing my spirit as I enter old age.”