WANT SOME REAL TRUTH AND RECONCILIATION? GIVE CANADA’S FIRST PEOPLES BACK THEIR STUFF

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

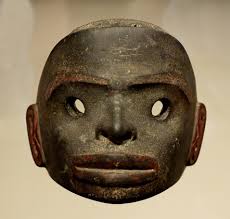

When the Nisga’a people of British Columbia’s remote Nass Valley sign their historic treaty with the federal and B.C. governments on Tuesday, there will be more at stake than money and land. The deal also provides for the return by Canadian museums of more than 250 Nisga’a artifacts, both sacred and everyday, that were bought or just plain stolen a century ago by clerics, collectors and government officials.

The unprecedented numbers represent a watershed moment in Canada with regard to repatriation — an issue that has rocked the international art and museum world. From the halls of the British Museum in London to the vaults of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, the debate over ethics and ownership has intensified in recent years. In the past decade, U.S. native groups have won legislation to have the bones of their ancestors returned, while internationally, the United Nations cultural agency, UNESCO, is pushing for the ratification of a convention on art and antiquities, known as UNIDROIT, that forbids the trade of anything obtained illegally, any object sacred to a living culture or religion and anything of “outstanding cultural significance.”

Although Canada has yet to ratify UNIDROIT, its museums have adopted a conciliatory approach to the question of repatriation.

“Initially, museum people looked at repatriation as a loss,” said Alan Hoover, manager of anthropology for the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, which stands to lose 150 of its 430 Nisga’a artifacts under the land deal.

“But when you look at the bigger picture, it’s an opportunity for growth. We will have a new relationship with the Nisga’a people. And I see it as very positive. It’s a relationship based on an equal footing — and this is different from what ever came before.”

Under the terms of the treaty, the RBCM will have five years to return the artifacts, as will the Museum of Civilization in Hull, Que., which is losing 107 items, roughly one-third of its Nisga’a holdings.

But the Nisga’a are not stopping there. This month, they will begin negotiations with the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, from which they will request almost the entire Nisga’a collection of 152 artifacts. The ROM, which has more than 40,000 aboriginal artifacts, many from outside North America, is not bound by the Nisga’a treaty. But it is mindful of a 1992 federal task force that urged museums to begin returning objects in their collections in consultation with the native groups claiming them.

A joint effort of the Assembly of First Nations and the Canadian Museums Association, this task force grew out of the opposition to The Spirit Sings,a 1988 exhibit at the Glenbow Museum in Calgary that brought together native artifacts from international museums without consulting Canadian groups.

In its report, which is not legally binding, the task force called for institutions to return illegally acquired objects and identifiable human remains to native groups requesting them. In return, the institutions could reasonably expect native groups not to seek legislation forcing them to do so.

“I used to think legislation was the only way to go,” said Chief Harry Nyce, an elected member of the Nisga’a Tribal Council in New Aiyansh, B.C. “But I’ve had second thoughts. I now think negotiation is the way to go. Attitudes have changed very much in recent years in respect to our artifacts in Canadian museums. Relations between natives and museums are good right now. Legislation might curtail it by putting people in court.”

In the era of repatriation, all museums are having to rethink their possessions.

“When you’re dealing with repatriation, it’s not an issue of whether or not we think they should be returned,” ROM anthropologist Ken Lister said. “It’s a matter of working it out with natives in a collegial way.”

This conciliatory approach is in stark contrast to that of many other countries. U.S. Indians, weary of waiting for action on their requests for the bones and sacred bundles of their ancestors, opted to fight for legislation instead. The 1989 National Museum of the American Indian Act and the 1990 Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act in the United States require all federally financed institutions to return human remains and associated artifacts to their aboriginal communities of origin.

In Europe especially, the descendants of victims of the Nazis have increasingly been demanding the return of looted art. Germany wants back the masterpieces confiscated as war reparations by Soviet troops. Last month, the British Museum returned second century Greco-Roman marbles to Turkey, which in 1993 won a court case forcing New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art to hand back the so-called Lydian Hoard of bronze, silver and gold artifacts.

Britain, meanwhile, has steadfastly refused Greece’s request for the marble friezes taken by Lord Elgin from the Parthenon in the early 19th century. And while Switzerland and Australia have agreed to return human bones and artifacts to U.S. Indians, Britain and Germany have refused.

Even if the tone in Canada is more genial, the course of repatriation can run very slowly. In Vancouver, the University of British Columbia’s Museum of Anthropology has had a repatriation policy in place since 1995. But while it has received hundreds of information requests, only about a dozen have involved the question of repatriation. From that dozen, only four have resulted in formal requests for the return of objects, and in the end the museum has returned objects in three instances.

For its part, the Museum of Civilization has processed about a half-dozen requests over the past 20 years, including the repatriation of a Plains Indian medicine bundle that the museum had presented to then-prime minister Pierre Trudeau in 1978.

In Calgary, the Glenbow Museum has processed 30 requests over the past eight years, although none has resulted in an unconditional return of objects. Instead, the museum has allowed 30 artifacts of native origin to leave its collection on a loan basis only.

Meanwhile, the ROM has yet to repatriate any object from its collection, Lister said, although it is looking at two other requests. The Nisga’a wish list, drawn up during four visits by band members to the museum in the past year, would represent “the largest request we’ve had in recent history.” Chief Nyce said he thinks the Nisga’a may get only half of it back.

But the request might have been even larger. The ROM’s collection includes three Nisga’a totem poles that, together with a Haida pole, are focal points in the main wing of the museum’s downtown Toronto building. The tallest is 24 metres — about four storeys — high. Named for Chief Sharp Tooth, a legendary Nisga’a warrior, it was erected in 1878 by the Eagle clan, of which Nyce, a commercial fisherman, is a descendant. Initially, Nyce and his people wanted the pole back, but they were discouraged by the prospect of having to cut it into pieces to get it out of the building. Instead, they plan to have contemporary carvers replicate the pole back home in the Nass Valley.

Repatriation is a complex issue. Some groups prefer that their artifacts stay in museums until they can build a place to preserve them in their own communities.

“Different experiences apply to different communities,” said Bob Boyer, a Metis artist and professor of Indian art history at Saskatchewan’s Indian Federated College.

“Some are prepared to accept things back, some are not,” Boyer said. “The elders say it’s better for the museums to hold onto our things until the Saskatchewan community is able to put together its own museum.”

Although the Nisga’a are asking the ROM for a wide range of items, including serving trays, chests and jewelry boxes, most requests deal with sacred and ceremonial objects. According to University of Saskatchewan archeologist Ernie Walker, it doesn’t make sense to return every single item.

“I think certainly in terms of sacred objects and things like that, medicine bundles for instance, [repatriation] is probably a very good idea,” Walker said. “However, I don’t think that we’re talking about repatriation of every single buffalo bone or something along those lines. . . . They want objects with real cultural value.”

Some bands want the objects back in order to resume ceremonial rites that were formerly outlawed or stripped of their proper regalia. They also need them as tools to instruct succeeding generations in the stories of their ancestors and to revitalize a sense of identity and belonging in their communities.

Alberta rancher Frank Weasel Head is a member of the Blood Nation, a Blackfoot-speaking tribe from Southern Alberta formerly known as the Kainai. Last November, he repatriated a medicine pipe bundle from the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of the American Indian in New York. Also called “thunder pipes,” the bundle was traditionally used when his people heard the first sounds of thunder in the spring.

The repatriation took several trips to the United States and 18 months of research and wrangling. It also cost the tribe about $30,000, Weasel Head said, but he felt it was worth every penny.

“These things are good for our young people, who are turning back to the traditional ways, learning our language and our spirituality,” he said. “We are finding peace in these things. They are changing our lives for the positive.”

As Gerry Connaty, senior curator of ethnology at the Glenbow, said: “To us, they are objects, but to the people concerned, they are living beings, they are like their children. They embody very many aspects of what makes their culture a reality.”

The Glenbow recently formalized its relationship with the Blood Nation with a working agreement that spells out the objectives of both parties. In March, the museum lent the Blood a number of ceremonial items such as headdresses and medicine bundles.

“At museums, we can perpetuate the object, but we can’t perpetuate its ‘aliveness,’ and First Nations can do that,” Connaty said. “In turn, the ‘aliveness’ of the [medicine] bundle will strengthen the whole community and make it a more viable entity.”

Natives depend on continued good will to get their property back.

“It doesn’t serve either group any worthwhile purpose to end up in court,” said Narcisse Blood, a member of the Blood tribal council. “And it has never been an option for us. We’re the ones who have to be patient. We’re the ones who have to fill in the forms and bite our tongues if we want to get our stuff back.

“But little by little, the process is working. There are people in the museums who want to help us. And so I’m confident that in the future we will get everything back.” — Deirdre Kelly