DANCE REVOLUTIONARY: ALVIN AILEY

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

The late American choreographer Alvin Ailey, who died of AIDS in 1989 at age 58, is being resurrected in filmmaker Jumila Wignot’s new documentary now playing in select theatres. The timing couldn’t be better. As the founder, in 1958, of a racially integrated dance company that foregrounded the Black experience, Ailey, in his way, was a visionary who anticipated today’s fight for racial equality across all sectors of society. His sensual and emotionally charged modern dance pieces, created for the New York-based Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, jumpstarted conversations about race at a time when segregation in the U.S. was a lawful practice— especially so in the American South where Ailey was born in 1931, to a 17-year old unwed mother. Those conversations have accelerated over the past year, goaded by disparities revealed by the pandemic. Ailey would no doubt be pleased about that.

A dance revolutionary, he consistently advanced the cause of civil rights through his art. He seduced rather than lectured, spotlighting joy, hope and redemption in lieu of lynching, murder and violent protest. Audiences, no matter their colour, were enraptured by his depictions of Blacks who, even in chains, soared above their difficulties, driven by faith, love and the strength of their community. Ailey had his own share of hardships and knew what it took to triumph over adversity. He knew success but he also knew misery and even despair. Wilmot’s bio-pic touches on his struggles with mental illness, for instance, and his need to keep his homosexuality under cover — his mother most definitely did not approve of his sexual predilections. A more thorough exploration of these themes can be found in ex-New York Times dance critic Jennifer Dunning’s excellent 1989 book, Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance. Here’s my review:

When Alvin Ailey was born, his head was so big his mother thought he had a defect. Until he was two years old, he refused to walk and had to be carried everywhere. So poor and malnourished that she weaned her son on sweetened bits of cloth called “sugar tits,” Lula Ailey had finally had enough when her baby grew too large to sit on her narrow hips.

“I put him down on the ground. And that little boy spun like a top. I said, ‘I thought you told me you couldn’t walk.’ He said I didn’t let him. He made two or three flips like he’d been experimenting.”

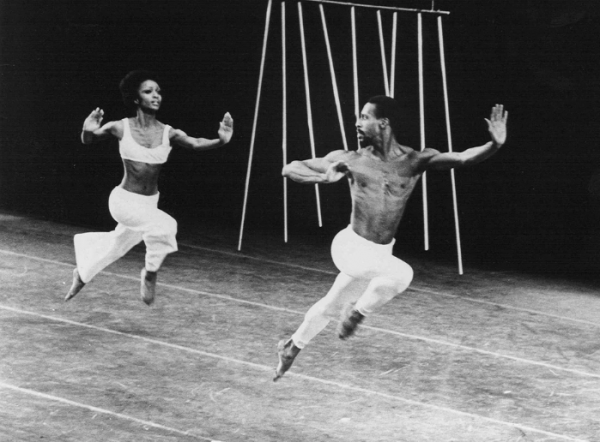

If Lula was looking for a sign that her son was normal, what she got instead was an omen of brilliance. His genius for dance, first shown on that hot day in rural Texas more than half a century ago, was fulfilled during a lifetime spent creating dances that celebrate Afro-American experience. Much of the choreography he made for his own Alvin Ailey American Dance Theatre poured spontaneously from a mind so nimble that he first thought to use it to study languages.

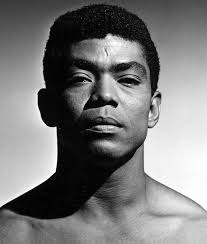

His talent was surprising considering he had very little formal training and little in the way of dance technique. While unskilled, he had “a distinctively sensual animal-like stage presence and prowl” that turned heads. He was what might be called a born natural.

When the creator of Revelations, a modern dance masterpiece, died in 1989 at the age of 58, more than 5,000 people braved a frigid December morning in New York to mourn his loss. His legacy included dances of emotional and stylistic power. But perhaps his biggest accomplishment was giving black ballet dancers opportunity. His decision in 1958 to create an all-black dance company came at a time when Martin Luther King was lecturing the United States about race relations. In his inaugural program notes, Ailey called the cultural heritage of Afro-Americans one of his country’s richest treasures.

In Alvin Ailey: A Life in Dance,veteran New York Times dance critic Jennifer Dunning tells Ailey’s story in the no-nonsense style that characterizes her newspaper writing. Dunning reports candidly on the flip side of Ailey’s sparkling persona, dealing evenly with the good and the bad, the beautiful and the ugly. While not quite a tell-all book — sometimes her carefully crafted prose is frustratingly prim and reticent — she does open the door on some of the skeletons in Ailey’s closet. The result is not only a meticulously researched document of modern dance history — modern American black dance history in particular — but a revelatory book that is chock full of illicit sex, illegal drugs and bedlam.

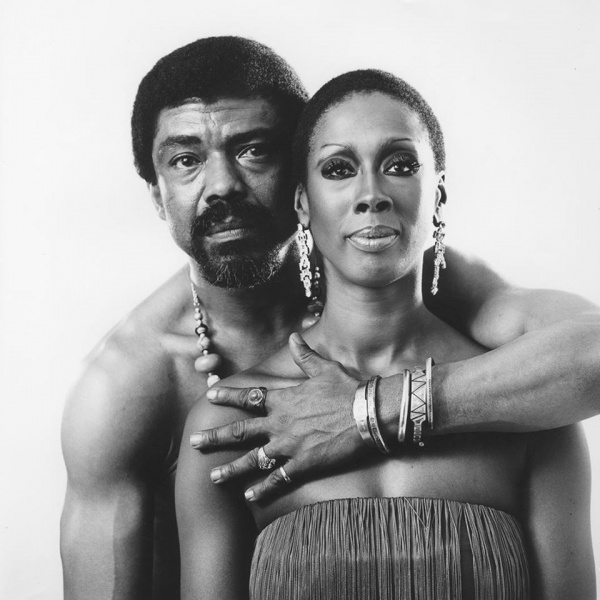

Dunning makes it official that Ailey died of AIDS. The true cause of death had been covered up by Ailey’s physician, his publicist and his dancers, chiefly Judith Jamison, a former Ailey company star. As Dunning points out, all were following his wishes. A secretive loner until the day he died, Ailey had not wanted the truth known for fear of hurting his mother, with whom he had never discussed his sexuality.

Ailey was undoubtedly warned off the subject following an early encounter with Lula at a performance of the late Lester Horton’s jazz dance company. It was 1954 and Horton, who had taught Ailey’s his first dance classes, had recently died. Ailey, a dancer in the show, was mounting his first works of choreography. He was wearing makeup. When his mother saw him backstage she slapped him hard. “From early on, movement was the one medium through which he could honestly express his innermost truths,” offers Dunning.

Her dense, driving prose drills deep into Ailey’s early years, exposing him as a bright but lonely child, devoted to his mother, the only parent he had; his father left two weeks after his birth. He lived intensely inside a fevered imagination entrenched in a world of make-believe. As an adolescent, he discovered books and devoured them. Among his own writings were purple poems about homoerotic desire. Dunning includes them in the book as well as some of the Gatsby-like notes he wrote incessantly to himself as reminders of the need for constant goal-making and self-improvement.

He was sexually aware as a teenager, finding himself turned on when tackled by an older boy who was ostensibly just horsing around. From then on he was never comfortable with his homosexuality, and lived a “secret” other life that was the opposite of the decorous world of the theatre. He indulged his repressed desires in orgies that he sought out in the sexually ambiguous world of Morocco or the dingiest corners of Manhattan’s 42nd Street, sharing his bed with derelicts.

Once when living in a penthouse apartment overlooking Central Park, Ailey rented the apartment next door in which to hide his sexual playmates. He had been planning to tear the adjoining wall down so he could have easier access to this seraglio of sin, but those plans were dashed when one day he suddenly went mad. Ailey had been stalking a young Moroccan he had brought to America and nicknamed Abdul. Rebuffed — Abdul thought Ailey was crazy — he went on a rampage, hurling both furniture and invectives. Ailey was taken away in handcuffs and confined to a psychiatric hospital for the rich.

His breakdown had been simmering for years. A manic-depressive addicted to alcohol and diet pills, at one point he was taking cocaine in his Perrier in the morning and in his champagne at night. His “gutter activities,” as he called them, were encroaching on his professional life, and as he became more successful he was finding it increasingly difficult to maintain a double life.

Yet people loved him and continue to love him and his dances. Wherever the Ailey company travels, it packs the biggest theatre in town. The works are already proving to be timeless pieces of art.

In the months before he died, Ailey was one of five Americans honoured with a prestigious Kennedy Centre award for lifelong artistic achievement. In his address, he spoke of dance “as the essence of what we’re about, the distilling of the spirit through movement.” Dunning’s achievement is that she makes that spirit soar