BALLET BENDER: KAROLE ARMITAGE STRETCHES THE CLASSICAL

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Combining Shakespeare, Stravinsky and the Sex Pistols in one potent postmodern dance package, punk ballerina Karole Armitage rips classical ballet out of the nineteenth century and repositions it firmly in the twenty-first. Her week-long performance at the Joyce Theatre just over, the woman who’s shaking up the dance world with flash and sass knows that her work as being nothing short of earth-shattering. “It’s sexy and existential at the same time,” she confidently says.

A fascinating choreographer as well as an enigmatic performer, Armitage syncs theatrical dancing with the sometimes garish sounds of rock and roll. But her background is minimalist. For five years she was a leading member of Merce Cunningham’s dance company. This association came after a short stint in the corps of a Geneva-based Balanchine repertory company, which in 1973 seemed the perfect place for a young Kansas ballerina just then honing her craft.

Armitage, now 33, sits in her dressing room after a performance, still sweating and slightly flushed even after taking a shower, and recalls her Balanchine days with a mixture of fear and loathing. She hated wearing a tutu; she hated being forced to act like a coquette, or a sweet-faced ingenue. When it seemed she would go mad if she put on another pair of pink satin slippers, she fled ballet for the earthier and more experimental world of modern dance in New York.

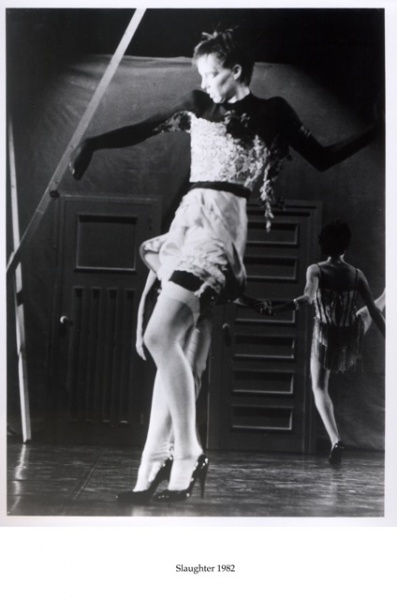

By the mid-seventies, Armitage had started to choreograph, attempting to radicalize dance in the way punk was then radicalizing popular music. “Punk music was big then,” she says. “It was something that was using ideas the way rock was, but reinventing them. I thought something like that could happen in dance, something that could be as emotionally exciting and powerful.”

A mover as well as a thinker, Armitage has created intellectually provocative and blatantly sexual dances for several companies, including her own, The Armitage Ballet, founded in May, 1986. She gained much attention last spring when it was reported that Mikhail Baryshnikov had frantically approached her to choreograph a piece for him for the forthcoming season of the American Ballet Theatre.

The result, The Mollino Room, received mixed reviews. “A pretentious monstrosity,” one critic said. “Strange and glorious, an exhilarating exaltation of dance,” another reported. Still, it gave Armitage a share of the limelight and made people take notice of someone who, in her own way, promises to change the face of ballet.

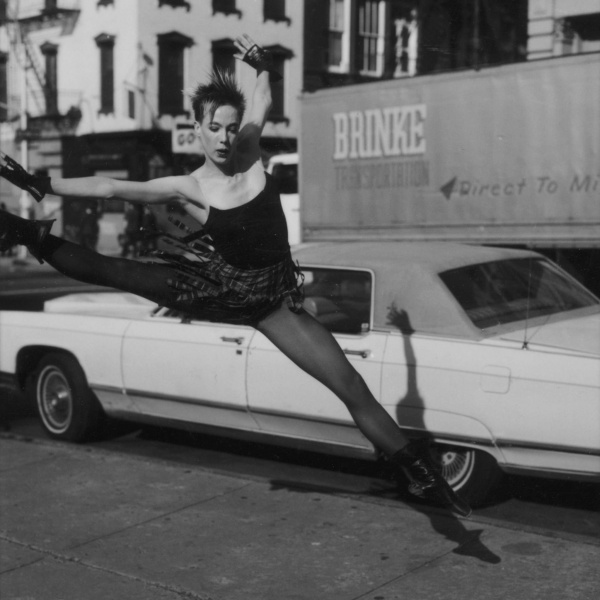

Armitage’s punked-out image has interested many people. Her hair is cropped short with the wispy bangs dyed platinum blond in sharp contrast to her dark, thick eyebrows. Her body is reed thin and usually wrapped in black. She wears black toe-shoes whose satin ribbons are dramatically crossed at the ankles. Because of this get-up, Armitage has been called the “punk princess of the downtown scene” by Vanity Fair magazine, and “a cult figure” by People. Armitage, who yawns when she says, “Punk’s dead. I’m embarking on a new phase,” doesn’t understand what the fuss is about. “I’m a classicist. I’ve always been making ballets.”

Ironically, the form that once made Armitage shrink in her tutu now gives her a profound sense of liberty. “I think the expressive tradition is more satisfying in ballet,” she says. “The way images are used and the fact that the technique is so far advanced makes it a more efficient and correct form to use than, say, modern.”

Armitage doesn’t stick to the rules, though, when using jetes and plies for her own peculiar purposes. “I like taking symmetry and rhythms and distorting them for new-found beauty and precision,” she says. “When I started out, there was really nothing like that in dance, though it was happening in other media, like rock music.”

Armitage says she loves music, and it shows in her work. Her Hipsters, Flipsters and Finger Poppin’ Daddies reads music like a painter might read a night sky. The rhythms are subtle but intelligently inflected to music by Anton Webern and Stravinsky. In one section, Armitage uses a beat poet’s reading of Marc Antony’s funeral oration in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar and has the dancers relying on their internal rhythms when moving about the stage. The reading, she says, “incorporates fifties beat existentialism with the Elizabethan melodic line and so provides a current counterpoint that shows how ballet can make progress, how it, too, can move with its time.”

Armitage, who lives with New York contemporary painter David Salle, is determined to ensure that ballet will not ossify in its own traditions, that it will stay fresh and vital enough to lend expression to trends as current (or as passe) as punk and gender bending. “I’m interested, “ she says, “in creating ballets that are a mix of innovation and expression, and that are about classicism moving with the times.”

(From the Deirdre Kelly archives; first published in 1987.)