Once Upon a Time in the Balkans

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

There was a thriving cinema industry in the country formerly known as Yugoslavia. Civil war and international sanctions crippled it beyond recognition. But directors stood defiantly behind their cameras, continuing to produce art at a time of unimaginable devastation. Here, from the archives, a story about how some of these mavericks — Serb filmmaker Dušan Makevejev among them — continued to create even as the bombs were falling.

THE pummelling of Yugoslavia by both internal and external forces over the past six years has not only destroyed a country, it has crippled a national film industry once booming, proud and internationally respected.

From 900 features produced in 1991 to just six last year, cinematic production in Yugoslavia and its successor republics has fallen drastically during the half-dozen years of civil strife. And understandably so.

“Because we spent all our funds on war, I guess you realize that we have very little for film productions,” said Yugoslavian producer Moma Mrdakovic.

Still, films are being made. Pretty Village, Pretty Flame, director Srdjan Dragojevic’s blistering account of the Bosnian war, was produced by Mrdakovic on a budget of $2-million (U.S.). One of 19 films showcased in Balkan Cinema: Home Truths, a diverse program hosted by the Toronto International Film Festival, the 1996 Yugoslav feature is quality filmmaking born of adversity. “I would say that any film being made in Belgrade right now is a miracle because the financial situation there is terrible.”

Economics tended to dominate the thoughts of nearly all the filmmakers who contributed to a round-table discussion of Balkan cinema in Toronto on Wednesday morning. The two-hour session covered such subjects as the commercial viability of Balkan film, the ethics of receiving funding from foreign nations and private investors, the financial health of domestic markets, the high cost of making films in countries strapped by international sanctions, and co-production treaties with countries such as Canada.

But amid all the talk about money, there was also a focus on of integrity, soul, artistic vision and the role of the filmmaker in today’s world.

“We are not the politicians, we are not soldiers, our only weapon is the camera,” said Boro Draskovic, director of Vukovar Poste Restante. “And we just react to the situation in our country, a difficult situation of war, and show the people who are suffering to the world.”

Draskovic himself suffered in making his film, a portrait of a once typical Yugoslavian family — half-Croat, half-Serb — torn apart by the madness of war. He filmed on location in Vukovar, the first city to be razed by the conflict, and was injured by gun fire. He survived, of course, as did his film, which for the past year has been travelling the international film festival circuit to critical acclaim.

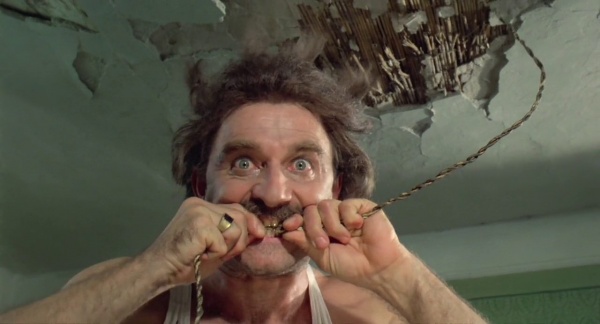

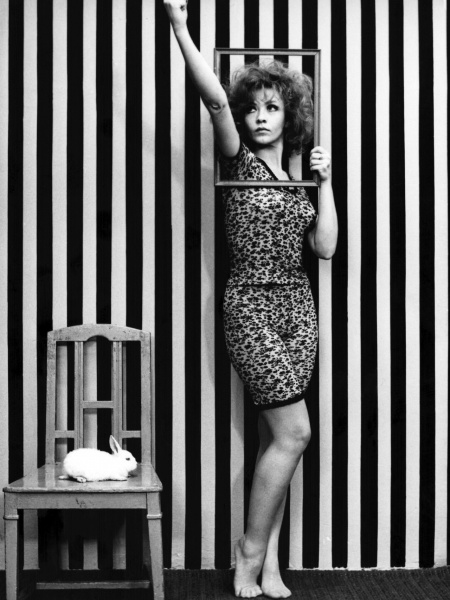

Balkan films have long had a certain universal appeal for the way in which they tell human stories with a unique and provocative commingling of tragic and comic elements. Director Dusan Makavejev, one of the masters of the genre, gained worldwide fame after Yugoslav authorities banned his seminal film WR: The Mysteries of the Organism in 1971. The ban continued for 16 years. Subsequently exiled, Makavejev took his film to the West where it was eventually seen by more than a million people internationally. His reputation set, he went on to make Montenegro and Manifesto and the Gorilla Bathes at Noon, all agit-prop films showcased over the years at the Toronto International Film Festival.

“I think it is totally provincial to think that our public is in our neighbourhood,” said Makavejev. “We’ve got a whole generation of filmmakers educated by world cinema, not necessarily by local situations, and even when inspired by local situations, we are capable of producing films that talk to others.”

Nenad Dizdarevic, director of Awkward Age, is part of the new generation of Balkan filmmaker reliant on foreign investment. He left his native Sarajevo in 1993 for France with the raw footage of Awkward Age in hand. He received assistance directly from the Minister of Culture and from French filmmakers who helped him mix and edit his film in their studios.

He was impressed by the solidarity of the French film industry, and also greatly appreciative, because without their help Awkward Age, said to be reminiscent of Truffaut’s The 400 Blows, would not have been made. “Concerning Bosnia, the country is destroyed completely and there is a lot of priorities and film is not as important as many other things,” Dizdarevic said. “So in the next 10 years, the next 25 years, no film from Bosnia can be done without international help because there is no money for making films.”

Still, Bosnian filmmakers should persevere because they have a great role to play in their country’s future. “During the whole time before getting out of Sarajevo all filmmakers did something during the war trying to testify about what was happening,” he added. “And I think once the history of the resistance of my town is written the role of the filmmakers will be a great one.”

Balkan films stand out because of this need to be relevant to the times. Creating socially responsible art is paramount to these filmmakers who, even if they wanted to, don’t have the luxury of making escapist films.

Rather, Balkan film is very much an adult cinema with grownups looking hard and long at the world around them. Also, in contrast to the Americans, who took decades to bring their Vietnam issue to the screen, Balkan filmmakers, especially those from Yugoslavia and surrounding republics, are responding immediately to their war. Indeed, it’s the theme that dominates nearly all the films from the region, including Slobodan Sijan’s Who’s Singing Over There? Made in 1980, the film is strangely prophetic of the calamitous breakup of Yugoslovia. What it shows, observed Borislav Andjelic, a Belgrade film critic in Toronto for the festival, is that “our directors and artists have a posititive energy to face the problems of their situation.”

Often they do so with little financial rewards. But several of the filmmakers said they weren’t in film for the money, but for the opportunity to express themselves and their ideas to the public.

“I personally don’t want to make a commercial film, said Zoran Solomun, director of Tired Companions. “I made two films for German television. I cannot tell you how many people saw these films . . . but I don’t have a bad conscience because my film didn’t bring money back. I communicated with people, I developed some new film language, at least I tried too, and if we think only in market categories we will not make art.”

Artistic integrity, or the need to be true to your vision regardless of the cost, is perhaps not unique to the Balkans. Yet it is a sentiment shared by most of the filmmakers. One who wasn’t sitting at the round table but who was invoked by one of his actors was Eduard Zahariev, the Bulgarian director of the poignant Belated Full Moon who died of cancer shortly after finishing the rough cut of his 1996 film. Itzhak Fintzi, star of the Bulgaria-Hungary co-production, described his late friend as a typical Balkan filmmaker in the sense that he never compromised his artistic vision. “He was always more faithful to the art of his movies than who would see his movies. He was a Don Quixote in this case who, at any price, wanted to express his own ideas and his own soul without compromise,” said Fintzi in tribute.

This commitment to making a thinking and feeling cinema, one that Makavejev believes can educate and entertain people the world over, is perhaps the Balkan’s greatest legacy to the world of film.

“Balkanization is a word that has always had a negative connotation,” continued Fintzi. “But I think the Balkans can fertilize the West with all the power of art.”