REMEMBERING CELIA FRANCA

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Life is short, dance even shorter. Now you see it now you don’t. That ephemerality is part of the allure. But it also tends to make dance itself, as a subject of cultural importance, less than substantial. Past triumphs are quickly forgotten, denying future generations a well-known legacy on which to build their own successes. Looking back is a way forward. Establishing a sense of history creates a kind of intellectual momentum that can drive dance towards levels of achievement not realized before. Who were the people who evolved the standards? What were their goals? Did they achieve them and how? Knowing what came before might not always inspire pride — there have been egregious practices and overbearing personalities which hurt more than helped the art form. But neither ignorance nor a denial of the facts can contribute to an understanding of what might need to be addressed and improved for real progress to occur. With this in mind, I go back into the archives to recall my appreciation of Celia Franca, the founding director of the National Ballet of Canada who died in 2007. Acerbic and aspiring, she was no wallflower. But her grit produced a small miracle— a classical dance company in a former British colony where ballet was as rare as a snowless winter. She stepped on toes but she also gave a swift kick to the pants of a Canadian dance culture. She dreamt big and even just for that reason it’s important to remember what she pulled off. She’s a starting point, a way to creating a sense of a Canadian dance history for others to build on and perhaps even better.

DEIRDRE KELLY

CELIA FRANCA AN APPRECIATION

A dancing dynamo; With a take-no-prisoners determination, she built the National Ballet from the ground up

Outsiders to the world of ballet, especially those bewitched by its hills and dales of satin and tulle, often persist in a belief of the art as populated by wisps of women for whom dance is a fairy tale performed in pointes. But Celia Franca was one dancing woman whose grit, passion and determination firmly put the lie to a portrait of the ballerina as delicate.

“She was an extraordinary tour de force,” says Veronica Tennant, a former National Ballet of Canada principal dancer, in remembering the woman who died on Feb. 19 in Ottawa, at age 85. “She was huger than we can possibly imagine, and you want to know what kind of person makes a pioneer? What exactly are the ingredients? What kind of combination of guts and glamour and combativeness and persuasiveness and brilliance does it take?”

As founder of the National Ballet of Canada when the country was considered to be a cultural backwater, Franca was a pioneer.

Single-handedly, she created a classical dance troupe in Toronto from the ground up, scouring the then arid artistic scene for homegrown talent that would allow her to create a ballet company that was truly national in character.

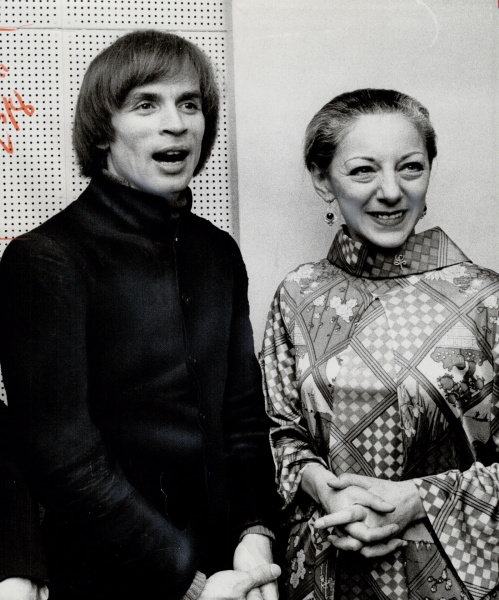

“She was very involved and very serious about taking Canadian dancers into the original company,” recalls Brian Macdonald, the award-winning Canadian choreographer whom Franca handpicked to join her fledging National Ballet in 1951. “I knew that from the studio I was in, in Montreal, she took six of us, which was incredible. It wasn’t the norm then. Then, you went shopping in Europe. But Celia didn’t do that. She looked over the Canadian landscape very carefully to find the talent.”

Ironically, that commitment to a domestic dance culture came from a woman who was brought to the colonies from her native England by a group of well-intentioned Canadian arts patrons (Eileen Woods, Sydney Mulqueen and Pearl Whitehead) who in 1950 looked to the motherland to give them direction in forming a national ballet company. Their search led them to Ninette de Valois, founder of the Sadler Wells Ballet (now the Royal Ballet) in London where, since 1941, Franca had gained prominence as a dramatic dancer.

As a soloist and ballet mistress with the short-lived Metropolitan Ballet, she had also begun choreographing for television. In selecting Franca for the job, there have been suggestions that de Valois may have seen an opportunity to rid herself of a potential rival with a powerful personality and formidable teaching skills.

It wouldn’t be the first time, or the last, that Franca would lock horns with others in her rarefied world of ballet.

One of her most famous and bitter feuds was with Betty Oliphant, whom she made director of the National Ballet School after establishing it in 1959 as an incubator of talent for the parent company. Graduates included Tennant as well as Karen Kain, Frank Augustyn, Nadia Potts, Mary Jago, Vanessa Harwood, Jeremy Ransom, Kevin Pugh, Rex Harrington and Kimberly Glasco — the major share of Canada’s dance stars.

Former Canadian dance critic John Fraser recalls that the rivalry between them was likely inevitable: “The competitiveness and prickliness between the two was tremendous. Their sensibilities were both out there wanting to be assaulted and insulted — and they did it to each other.”

And yet her professionalism got the better of her. Sergiu Stefanschi, a respected National Ballet School teacher who danced in the National Ballet in the early years under her direction, recalls Franca as being acerbic, yes, but also so fully committed to her art form that she inspired others by example.

“Miss Franca wanted to be in the studio all the time. That’s what she felt her message was — working very hard, never quitting on an idea of excellence, always having the highest of standards,” says the graduate of St. Petersburg’s Vaganova Academy, where for three years he was a classmate of Rudolf Nureyev.

His connection to the great Russian helped pave the way for Nureyev’s arrival to the Toronto troupe in the 1970s when Franca, deeply impressed by his talent but ultimately weary of his tantrums, brought him into the company to stage a $400,000 production of The Sleeping Beauty.

She was taking a huge financial risk, but it paid off handsomely, pulling Canadian ballet out of obscurity. Observes Fraser: “Her network of international contacts helped the company soar at the same time as the dancers at the school started making a big impact on the world as well. Kain and Augustyn won the silver medal at Moscow under her direction and that was a big deal. It put Canadian ballet on the map. It was an extraordinary achievement.”

While a generous teacher, Franca could be blunt, brutally honest and also cruel in her comments. “She was difficult. She wasn’t an angel. But I adored her and respected her very much,” says Mary McDonald, Franca’s friend for the past 49 years. The two women met when McDonald, now retired, was senior pianist of the National Ballet. Working alongside her for the 25 years Franca was head of the company, McDonald got to know intimately both her strengths and weaknesses.

“When I first met her I had the wit to know that she was a force,” McDonald recalls. But when we really became friends — and it took two years for us to get to know each other — I realized the extent of how diabolical the work was to start this company. So she had to be ruthless. She couldn’t have been otherwise to do what she needed to do.”

It’s that attitude, for which Franca gave no apology, that has prompted Glasco in the days since Franca’s death to think of her former coach as the personification of ballet past: “People are saying that she ran the company with an iron fist, that people were frightened of her but that they respected her. But why do you have to have a boss like that? Dancers like to dance. You don’t have to be cruel to them. It doesn’t make them try harder. It only makes them quake with fear. It shows how archaic a world she came from. And now that she’s gone, the future of ballet, you have to hope, will strive to become more enlightened.”

An end of an era, indeed.

Eventually leaving the National Ballet — which came to be run by a succession of directors, including Erik Bruhn, whom she had first brought to the company to stage La Sylphide — Franca relocated to Ottawa with her third husband, James Morton, a clarinetist with the National Arts Centre Orchestra.

Even in advanced age, she felt a need to stay with ballet, and nurture young talent wherever she found it. With Merrilee Hodgins, she directed the School of Dance in Ottawa and, until recently, was frequently in attendance at dance performances within the capital. NAC dance producer Cathy Levy says that the years didn’t wither her appreciation of the art nor dull her wit. “She was very funny and she had strong opinions and was never afraid of her opinions. I remember recently that she came to see a contemporary dance piece. There was nudity. She turned to me and said, ‘Darling, there are parts of the body that you just can’t choreograph.’ ”

But she was only half-joking. Deep down, Franca believed that not only could you make a body dance, you could make a country sit up and take notice.

“Her legacy,” says Hodgins, who was with her the day before she died in hospital, “is her commitment to the dancers of tomorrow. That was what Celia was all about — the next performance and the next young dancer coming along. Her passing represents an end of an era. She represents an amazing chapter of Canadian history. She fought for all of us.”

The dancer as dynamo.