Mamma Mia! Sophia Loren is Back!

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

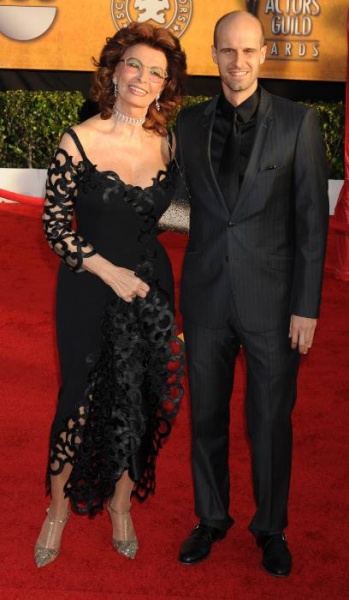

Sophia Loren has a new movie out—at the age of 86. Directed by her son Edoardo Ponti, “The Life Ahead” is a Netflix drama (the pandemic prevented it from having its scheduled debut at a cinema in Rome) that though on the small screen is being heralded as a big deal. This might be the film that gives her her next Oscar. And about time. The last one was more than 50 years ago. But I digress. Reading about her just now in The Guardian newspaper where she’s described as imperious and diva-like — but how else would you expect a living legend to be?— I remembered the time I interviewed her and yes, imperious and diva-like are pretty much right. The recollection is worth bringing up again because the film she had come to the Toronto International Film Festival in 2002 to promote — “Between Strangers” — marked Edoardo’s directorial debut, and the first time he worked with his famous mother on a feature. And so here they are again, 18 years and many projects later, still collaborating. I want to say I predicted the success of the mother/son team as artistic partners all those years ago. To prove it, I rooted about in the archives and found that story. I now want to share it because, all modesty aside, it is pretty good and that’s because of Sophia Loren herself. You’ll need now to read it to see what I mean. One thing not in the story but that really happened behind the scenes is that I was pregnant with my daughter when I sat down with Sophia Loren in a Toronto hotel room that day. The actress gave me a bit of a hard time but when the conversation was over she unexpectedly reached out to me with a manicured hand heavy with gold bangles and put her hand on my womb and blessed it. So there you have it— the fertility goddess herself, the Venus of our time, venerated me and my unborn child. As I mention in my piece her maternal instincts are as potent as her sex appeal. And that daughter of mine? Imperious and diva-like. So thank you Sophia Loren. This one’s for you:

My god!,” shrieks Sophia Loren, a ringed hand flying into the air. “You said you’d take just one photo! You have taken now, how many?”

The besotted one has taken a lot — but what man has ever been able to resist this Siren of the Screen?

(Out of earshot, he tells me he was clicking away because he wanted to get all of her, especially her legs, to show how sexy the Italian actress — a legend in her own time — remains at the incredible age of (gasp) almost 68. Her birthday is on Friday).

Her shapely gams are today sheathed in sheer hose and a pair of bright red high-heeled shoes. While the footwear screams erotica, the ankles are crossed primly at the ankles throughout the 20-minute interview — one of many Loren is giving in Toronto in service of her younger son Edoardo Ponti’s feature film debut, Between Strangers, in which she stars. The image, it turns out, is vintage Sophia: a sex goddess with the primal instincts of a mother. All the wires are crossed at once. No wonder members of the male persuasion run amok when around her.

Ponti, her second son (Carlo, Jr., the first, is guest conductor with the Russian National Orchestra and music director of the symphony orchestra in San Bernardino, Calif., close to one of the family homes), doesn’t see her as the sexpot: “Tell me what son could say that about his mother?” She is instead his muse, his mentor, his Madonna of the Movies who inspired his film on a deep, subconscious, I-love-you-mamma level.

The Italian-Canadian co-production about three women whose lives are dramatically interconnected was shot entirely in Toronto last year and released in Italy on Friday. It also had its North American premiere screening Friday night at the Toronto International Film festival, where critical reaction was mixed — but not for La Sophia.

Everyone is hailing her performance as Olivia, the repressed, downtrodden wife of self-absorbed, wheelchair-bound John (Peter Postlethwaite) as Oscar-worthy.

Dressed down in a shapeless housedress, and with her face seemingly free of makeup (though it took two hours of makeup every day to make her look worn and wrinkled), Loren lays herself raw. Her style is restrained and economical; much of the acting comes not from words but from haunting eyes and a shuffling body language that speak poignantly of the tormenting secrets Olivia keeps locked inside herself.

“I was not Sophia Loren when doing this role,” she pronounces, as if that other woman was a distraction she needed to keep at bay, to let the more serious work of acting take over. “But I felt at ease right away. I felt that it was something that pleased me and felt right doing it.”

Her 29-year-old son allows that when he wrote the part he didn’t realize he had his mother in mind. But as the role emerged on the page he saw that it was her (different circumstances, of course) but in essence the same shy, vulnerable, introverted — “but capable of showing great strength when it is necessary” — person that he has known his entire life.

Shy is not the word that springs to mind when describing Loren. But while facing both the journalist’s microphone and the cameraman’s relentless whiz and click, Loren twists her fingers nervously in her lap and demurely looks away into her glass of water whenever there is a lull in the conversation.

Except for the momentary flash of peevishness shown yet another member of the opposite sex who can’t quit buzzing about her beauty, Loren declares that her best quality, now that she is a (sultry) senior citizen, is patience:

“I am much more tolerant and determined about what I want in life — peace, serenity, tranquility: the good things. I always look around the corner to see what will be coming my way. I am very optimistic.”

It’s a virtue that likely stems from the fact that Loren, despite having a difficult life — she was born illegitimate in the slums of Pozzuoli, outside Naples, and suffered great hardship during the war years — has overcome her obstacles by dint of hard work and perseverance.

She has out-gloried the other Italian bombshells of her day — Claudia Cardinale, Monica Vitti, Gina Lollobrigida. They are today nowhere to be seen, but Sophia is still adored. Witness the adulation that swirled around her in Toronto Thursday night when she graced the opening of Viva Italia, a 40-day celebration of Italian style at Holt Renfrew, with her sparkling Armani-gown presence, and again at Friday’s gala screening of Between Strangers.

Crowds moaned and waved and cheered as if royalty were in their midst. Grown men and women said they had goosebumps just being in the same building with her.

Loren graciously took in the attention and then returned the affection with a Queen-like wave of the hand. The fans ate it up.

“When you go to these kinds of events you have to smile and be content that people love you. I’m very honoured that people have respect for me, and I have great respect for them. It’s a love affair.”

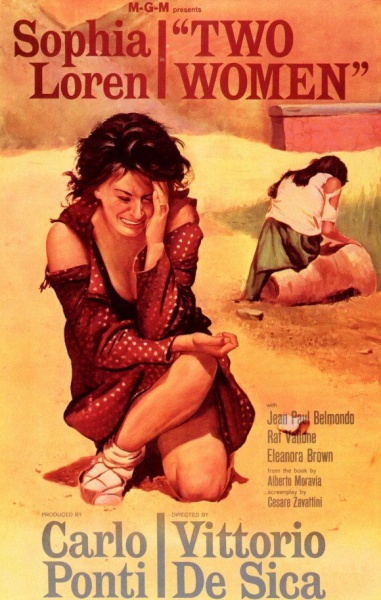

Loren is still on top of her game although it has been 40 years since she won the Academy Award for La Ciociara (Two Women). Hundreds of movies line her career, most memorable being those in which she played alongside Marcello Mastroianni, such as A Special Day, the 1977 film that Ponti says is his favourite Sophia Loren film. (“It’s the only other film where she has the introversion she has in my film; I wanted to draw on that.”) But most are best forgotten.

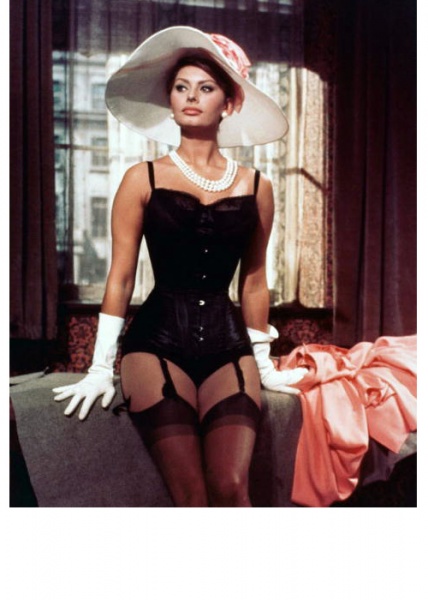

Before Robert Altman cast her opposite her beloved Mastroianni in 1994’s fashion spoof, Pret-a-Porter (she got to revive the corseted sex-symbol persona with irony-laden gusto), Loren was in danger of becoming the Italian Joan Collins — sinking into a series of campy television movies. Early last decade, she turned — incongruously enough for an exotic looker — to shilling eyeglasses for a living. Yes, they are fashionable specs (she wears a pair to the interview — almond lenses with deep purple arms that vividly set off her tawny olive skin and mane of auburn hair). But surely she doesn’t need the money?

Her producer-husband Carlo Ponti (turning 90 in December) is said to have amassed a fortune for the family. He has produced most of Loren’s films during her 50-year career (he met her when she was 15, the winner of an Italian beauty contest he was judging) and in addition has a sizable art collection (including the biggest private collection of Francis Bacon) worth many millions of dollars.

You get the feeling that Loren is a bit like the late Rudolf Nureyev, another legend born penniless who worked extremely hard to get to the top who never felt he had earned enough — neither money nor accomplishments. These people are driven to prove something their whole lives. Loren, however, bridles at the suggestion that she has ever felt the underdog.

“I have never felt the need for people to acknowledge me. I work very hard and I accept myself for who I am. I like who I am — very much.”

She allows that that self is multifaceted — there is the screen diva, the sexpot, but also the wife and the devoted mother, the cook (she has recently published her second cookbook) and the good Catholic who still makes her own bed in the morning.

The proudest moment of her career belongs to 1961’s Two Women,which she says catapulted her to the big time. Until she won the Oscar, she was a pretty face and a magnificent body — more an object of desire than of respect. This irked her.

“Once I did that film I was a real actress, not just a sex symbol. I was offered roles I had never received before. it was the first important film of my career. It changed my professional life completely.”

Still, she is known as “the face that launched a thousand ships,” as co-star Mira Sorvino says later. “They tried to play it down in the film — they lit her harshly, put her in a grey wig. But she still looks amazing, doesn’t she? She is like a head on a ship. There’s something incredible about her presence. She represents an image of womanhood, a cultural archetype of feminine grace and strength and sensuality. She is like Athena. Her power is ageless.”

Sorvino probably meant to say Aphrodite, goddess of amore. Athena is the breast-plated one, the protectress, goddess of war. Or maybe it wasn’t a slip. Loren is a tough cookie. She fiercely shields her privacy during the interview. Any questions that seek to probe beneath the protective armour (legs crossed tight, gaze direct) she deflects quickly and sometimes stingingly.

She is like Teflon — other people’s perceptions of her just won’t stick. She is and always will be her own woman: “I can look at myself in the morning every day and say, not bad, not bad at all.”