WHERE THE WILD THINGS ARE

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

In a remote ranger station in a faraway corner of South Africa’s Kruger National Park that slithers along the border of Mozambique, bushbucks and monkeys are regular visitors. A leopard nightly patrols the neighbourhood populated by elephants and hippos, baboons and lions and, in a modest buttercup-yellow house, a popular memoirs writer, her game warden husband and their three blonde daughters. Twilight is brief and darkness falls fast on the largest wild animal reserve in South Africa, whose vastness would fill Wales. The bushes come alive with snorts and grunts and snarls that can scare a human half to death.

But lately life sounds different in the ears of Kobie Kruger, author of the The Wilderness Family, a best-seller in her native South Africa and released for the first time in North America last week. Instead of the earth-shattering growls of the king of beasts, a close companion during her years in the wild, Kruger hears the whirr of cash registers racking up sales for her gripping book — a kind of Born Free of the new millennium.

In her trek across the continent on a promotional tour that has had her in 10 cities in as many days, Kruger has been eating in candlelit restaurants, staying in five-star hotels, and signing copies of The Wilderness Family in high-end bookstores with Mozart wafting overhead from discreetly positioned speakers.

The civilized life, and it has her spooked.

“I’m not used to staying in hotels,” confesses Kruger, wide-eyed as a child regarding her first Christmas tree, who walks gingerly over the plush oriental carpeting at Toronto’s King Edward Hotel. “It’s all like a palace to me.”

When she sits down to dinner a few minutes later the wonderment continues.

“Oooooh,” she squeals, awestruck by such dishes as warm hazelnut crusted goat cheese with roasted peppers and balsamic glazed figs and Mediterranean tuna tartar on crisp olive bread. “Look at all the choices. I usually don’t know what any of these things mean.”

Kruger’s naivete (she giggles a lot and speaks in whispers) is touching for a woman who is 52, more so because genuine. No relation to the founder of the park that was her home for 17 years beginning in 1980, Kruger is most comfortable roughing it in the bush.

She was born in the Northern Province on a farm where her father, the late Jamie Uys, was the director of the internationally acclaimed film The Gods Must Be Crazy. Husband Kobus (his name is a masculinized version of hers) was also born on a bushveld farm but they didn’t meet until both were students at the University of Pretoria where she was specializing in African tribal languages.

For their first date, Kobus took her to see the 1966 movie Born Free. It was destiny. Kruger has always preferred to live happily oblivious to the concrete jungles of civilization.

Her chandelier has long been the starry sky of the African plains. Her music, the roar of beasts with whom she has shared her heart, her home, her bed.

She has never heard of Ally McBeal. And until earlier in the day, when her publicist introduced her to flavoured coffees, she was blissfully ignorant of Starbucks. “I discovered something today,” she says in the lilting accents of her native land. “A latte!” She pronounces the word as if it were a lollipop, with a delicious lick of the tongue.

In many ways she resembles a World War Two survivor, rescued, after 40 years, from a South Pacific island, who encounters pop culture for the first time.

“Yes, it is very much like that,” Kruger allows. “Where we live now, in the East Cape, there is a city 90 kilometers aways from us where we go once every three months to buy books or CDs and clothes. My husband is my wonderful chauffeur. I can’t drive into a city anymore. I wouldn’t know how to navigate it.”

But a dangerous waterway infested with crocodile and angry hippos, which regularly overflows its banks, is another story.

Kruger expertly handles its turbulent currents in a rowboat that for almost a decade was her chief source of transportation.

Mahlangeni, the Tsonga word for meeting place, is a heart shaped basin of sand and forest nestled between the Little Letaba and the Letaba rivers where Kruger lived with husband Kobus and their three daughters.

Big-toothed predators regularly jostled her boat, hoping to topple her and her brood into the muddy waters for a quick meal.

Kruger, whose slender frame makes her look delicate as a bird, carried a shotgun with her at all times. One big enough to throw her backwards to the ground when she used it for protection.

In her crisply written book, Kruger describes a particularly hair-raising event involving a pair of national servicemen who failed to heed her warning not to set off in the boat without her. She had just returned from fetching her shotgun from inside the house when she saw them travelling headlong into danger.

By the time I reached the water’s edge, the boat was already half way across the river. And then I saw it: that telltale V-shaped ripple on the water, coming downstream and heading directly toward the boat.

I raised the rifle and took aim between the ripple and the boat, but felt too scared to pull the trigger. I had never fired over such a distance — about 80 meters — and was terrified of hitting one of the occupants of the boat. If I moved my aim I would risk hitting the hippo.

Suddenly the hippo surfaced and made a wild lunge for the boat — a thing I had never seen him do before. Filemoni yelled at the hippo and doubled his rowing speed. The hippo followed with grim determination, seemingly intent on annihilating the boat once and for all. I raised the rifle and took careful aim at a point between the hippo and the boat, but before I could squeeze the trigger the hippo’s head appeared in the sights. I started trembling and couldn’t steady my aim . . . The hippo lifted his head to check the distance before hurling himself onto the boat. I stopped breathing, and the bead finally settled into the foresight. There was no time to yell at Filemoni and the soldiers to duck before I squeezed the trigger. As the air exploded, silencing the cicadas and the birds, the recoil punched me so hard in the shoulder that I almost sat down on the ground. A fountain of water erupted just in front of the hippo’s open mouth, soaking the occupants of the boat. The hippo reared his massive head, slammed his mouth shut and submerged.

She was always loath to kill any of the animals she and her husband were obligated to care for. She even learned to sidestep poisonous snakes that entered her bedroom during the night, coiling in to the grooves of her wooden headboard or lying in wait in the middle of the floor. Such was the case with a particular Mozambique spitting cobra that forced her to lock herself into a bathroom out of fear of its lethal venon that it could spit accurately at a distance of two metres into the eyes.

If they found orphaned animals they took them in and nursed them to health before releasing them back in to the wild. The first in a series of foster children was a pesky honey badger that slept with Kruger on her pillow. A serval — a wild cat smaller than a cheetah but much larger than the average domestic tabby — came to Kruger with a broken paw and a foul temper, both of which she tempered with love and devoted kindness. Other strays included a bantam chick, a squirrel, three wart hogs, two scrub hares and a marsh owl.

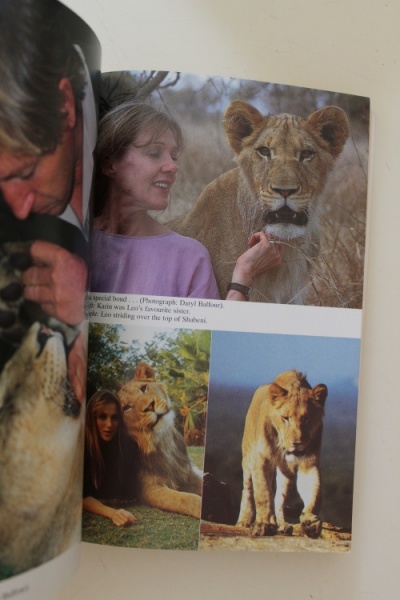

But the most significant addition to the family was Leo, the appropriately named lion, who entered Kruger’s life when her husband found him, abandoned by his mother, umbilical cord still wet, in a ditch at the side of the road. Says Kruger in the chapter Nobly Born, “[N]othing could have prepared me for the intensity of emotions and the level involvement that come from fostering a lion.”

Kobus and his men searched for the lioness but failed to find her. He believed she may have gone hunting at a neighbouring farm and been killed.

Park policy prohibits the keeping of wild animals in captivity, so the Krugers had to seek permission to raise the cub that meowed pathetically for his caregivers if they left him alone. Kruger writes, “The problem with large carnivores is that once they have been hand-reared, they are unable to fend for themselves in the wild unless an appropriate rehabilitation program can be provided. A male carnivore also needs a hunting territory not yet occupied by other carnivores of the same species. A lion, being a social animal, also needs hunting companions to help defend the territory. Reintroducing a hand-reared lion into the wild, or at least finding a suitable alternative home for it, can be a complicated business.”

The Krugers cared for Leo tenderly, treating him as a member of the family. His best friend was Wolfie, their pet dog, who tried to teach Leo to hunt, to no avail. He ate voraciously, the Krugers sometimes skinning animals in front of him to give him an idea of how it’s done. No deal. Still hand-fed at 19 months, which is when he left the Krugers to live in Pamuzinda, a pioneering lion park outside Harare, Zimbabwe, Leo had grown to 300 pounds. “It was the hardest moment of my life,” writes Kruger about saying good-bye to her “baby.”

We couldn’t bring ourselves to tell Leo that we were leaving him. So we just hugged him a lot and stroked his fur.

Eventually we gave him his chicken. He was surprised and delighted at the sight of his favourite fare — but only for a moment. He knew something was wrong. He sensed our mood, and his eyes were full of questions.

“We have to go now,” Kobus said finally. He gave Leo a last firm hug, patted him on the back and then walked to the truck and got in.

Hettie [their eldest daughter] hugged Leo wordlessly, spilling tears onto the top of his head. Then she too got in the truck.

I fetched my pillow from the truck and gave it to Leo. He slumped to a crouching position, clutching the pillow to his chest. And when he looked at me, there was comprehension in his eyes. He knew then that we were leaving.

Kruger has tears in her eyes as she remembers her lion with slow jabs at her tomato salad. Leo died last year, at the good old age of 8 (which is 60 in lion years) after being attacked by two other lions relocated to his park from their own territory. They were nervous and on edge. Leo, always a pushover (a true cowardly lion), was no match to them when they rushed, fangs at his throat.

But before he died he sired several cubs with two wives. This week, one of his daughters is giving birth to her own brood. “Leo would have been a grandfather,” Kruger says with a twinkly eyed smile.

Even though her husband was almost killed by a lion attack in the park, Kruger says that lions are man’s most faithful friend, when given the chance.

“They are capable of complete love and trust in a human being,” she says. “Our lion loved us too much. It was too poignant for words.”

Leo, as with the other animals Kruger got to know during her years in the bush, taught the Krugers about how to live in harmony with all of creation.

Today, living in South Africa at Paradise Beach, she lives with magnanimity in her heart. She swims with the dolphins who cavort just beyond her doorstep. She stares into their eyes and senses the intelligence and empathy deep within.

“Man would die of great loneliness of spirit if there were no animals on earth to keep him company,” Kruger says. “Just think how bereft we would be.”