BALLET’S DIVERSITY PROBLEM

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

The race riots that have erupted in the US in the wake of the murder of black man George Floyd by Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020, have sparked protests around the world, with even ballet dancers joining the fray to lend their voices to calling for an end to systemic racism at all levels of culture, including the arts.

That the ballet remains overwhelmingly white is no illusion. Decades if not centuries whitewashing in the name of art remain in place despite recent advances made by black ballerinas like Misty Copeland, Michaela DePrince and Canada’s own Céline Gittens (significantly dancing lead roles not here but overseas in Britain as a principal dancer at Birmingham Royal Ballet) who now command their spotlight in their respective companies. Their success isn’t tokenism. But that’s not always the case.

Even in the face of the race riots are ballet companies that are choosing to do and say nothing. They do so at their peril. The fallout can be disastrous from a PR and brand perspective, potentially impacting an organization’s bottom line should audiences, patrons and sponsors choose to withdraw their support of a company perceived to be tone deaf to allegations of racial bias. On the inside, recalcitrance can be seen as a lack of leadership, affecting dancers’ morale and creativity. This is the case at the National Ballet of Canada whose silence on the issue — until a company member of colour finally called them out for it— has been interpreted as indifference at best and racism at worst.

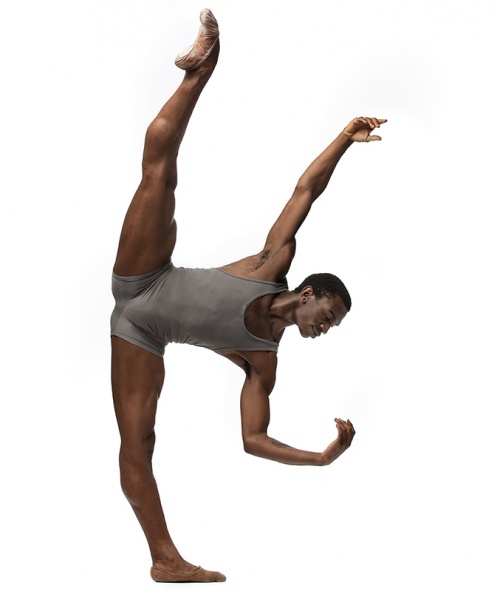

Nicholas Rose, a corps de ballet dancer at the National Ballet of Canada, has as of June 1 been posting videos of himself lambasting the Toronto company for not once reaching out to him or any other dancers to check in with them or offer support during this time of racial unrest. The posts express pain as well as frustration and feelings of humiliation brought on by both present and past practices at ballet, including the airbrushing of his black facial features in company photographs — a charge the NBoC publicly denies. There are also allegations of racial profiling and of being confused by a leading member of the artistic staff with another dancer who is shorter in stature but also black, the suggestion being all people of colour look the same.

Rose’s extensively viewed Instagram posts were recently spotlighted by New York’s Dance Magazine in its own coverage of ballet’s diversity problem, drawing global attention to the company’s maladroit handling of a contentious issue. The perception is that the Toronto company has not just ignored the emotional and psychological needs of its dancers. It had refused to move with the times in addressing the systemic racism entrenched in the art form. Ironically it has not shown itself to nimble enough to navigate what to my seasoned eye is a very old problem. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

I’ve been writing about racial bias at the ballet for years — in my Ballerina book and in newspaper articles like the one reprinted below, dating to 20 years ago. Sadly, little appears to have changed since then. The company still has no black principal dancers and still has a repertoire that is generally white, old, European and out of touch. A company more 19th century than 21st. Read it and weep:

ARTS ARGUMENT

It’s time to raise the barre

LAME-DUCK BALLET? Blame whomever you want for the National Ballet’s deficit troubles, but things would be different if it could see beyond its nose.

DEIRDRE KELLY

The tutus are in a knot again at the National Ballet of Canada — but the trouble may be more profound than all the bickering makes it appear. Like Eaton’s, the National Ballet has lost touch with the people. Its problems are more sociological than esthetic.

This week the company announced that it is yet again in the hole, having accrued a $1-million deficit for the performing year that ended June 30. The accumulated debt for Canada’s largest classical dance company now stands at a whopping (and unprecedented) $3.8-million. The National’s executive is blaming it on troubled times for ballet. Critics of the organization say poor management is at fault, and wonder how much money the company is willing to lose to block ousted ballerina Kimberly Glasco’s request for reinstatement.

The real reason for the company’s declining fortunes may be much deeper: The National Ballet is sadly out of step with its time and place. Instead of presenting works that reflect the cultural diversity of urban Canada, it concentrates mostly on works from other centuries and other countries with little or no connection to Canada at all.

One of the reasons artistic director James Kudelka was hired in 1996 was to ensure that the National develop an identity all its own. But what has he done so far to satisfy that mandate? Let’s see . . . expensive remakes of Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, the latter set in Czarist Russia, the former unfolding in an ancient court in a distant land. Last season, he restaged The Fairy’s Kiss for the company, a ballet whose classical vocabulary borrowed heavily from Marius Petipa, a 19th century Russian choreographer.

In between, Kudelka has brought to the National Ballet a clutch of contemporary ballets — The Four Seasons, Musings, Desir and Cruel World among them. In some instances the freshness of the choreography, a merging of classical and contemporary idioms, has given hope that Kudelka is forging a uniquely Canadian dance style. But these works have still failed to stop the National from hemorrhaging both revenues and audiences. So what is really going on?

Instead of pursuing his goal of redoing the Tchaikovsky canon (this week, Kudelka suggested that The Sleeping Beauty will be his next full-length project) perhaps the company’s chief choreographer should be thinking of creating or commissioning works that reflect the real Canada.

Think about it. Nights at the ballet could feature work inspired by East Indian or Native Canadian culture. The country’s craze for social dances like swing and tango and salsa might also fuel new creations that meld the classical steps of old with a sensibility that is more of today.

Other choreographers have embraced their times with abundant success, and they are among the few dance artists of the 20th century to have been labeled geniuses. They include George Balanchine, the late, great choreographer and artistic director of New York City Ballet, who revitalized academic dance by introducing to it the jazz steps and popular dances he witnessed on his forays into the black nightclubs of Harlem.

Mats Ek of Sweden, a choreographer who is still very much alive and kicking, takes the classics and boldly reworks them so that they are both relevant and interesting to today’s audiences. His Giselle takes place in a psychiatric ward; his The Sleeping Beauty is set among junkies; and his Carmen (which the Lyons Opera Ballet brings to Toronto next month) is a cigar-chomping feminista.

If the National Ballet were to revise its repertoire to attract new audiences it would also have to go one step further — altering the complexion of its dancers. With a few exceptions, the National Ballet is a sea of white limbs and faces. There are occasions (the National’s current Western Canada tour being one of them) when colour does tinge the ballet blanc, but rarely. And in general, those who go to the ballet are reflected in the narrow racial makeup presented on stage. So no wonder audiences for the company are thinning. Canada is no longer the exclusive European club it was when the company was founded nearly 50 years ago.

More people would likely go to the National if what they saw there reflected something of their own reality. When the National Dance Theatre of Jamaica recently performed in Toronto and Ottawa, the venues where they played were sold out. At Toronto’s Ryerson Theatre, the demographic composition was more than 95 per cent black. You almost never see large numbers from the city’s black community at the National. What does the National have to offer them?

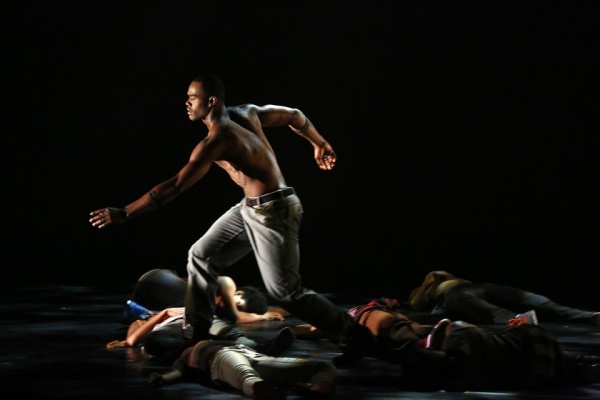

But again they are out in droves when the Dance Theatre of Harlem and the Alvin Ailey Dance Company visit. These are troupes that feature blacks among their ranks and whose choreography, while rooted in traditional disciplines like ballet and modern dance, makes room for a range of influences from the African diaspora.

The National Ballet would do well to follow suit. It is obvious the ship is sinking. Box-office revenue is down, audiences are staying away (even for The Nutcracker, a former cash cow) and patrons are either cancelling their subscriptions or reducing their contributions because they no longer feel the National Ballet is serving the needs of the community. The company, rather than heeding criticisms, goes on the defensive. Even though it has lost money over the last three years, during an economic boom, it wants to say that everything is fine. We lost money, said Kudelka this week, but we had some great reviews.

Another cultural institution that found itself floundering years ago was the Canadian Opera Company. But instead of going to great lengths to protect the status quo, the COC took a hard look at itself and decided to initiate some changes. It went into the community and hired some of the sharpest talents in our midst to turn their skills to the opera. The next thing you know, the COC is one of the most succesful arts organizations around.

Like the National Ballet it peddles an ancient art form. But the crucial difference is that the COC is drawing its audiences from a much wider cross-section of society. It surges forward while the ballet company lags behind. If serious changes are not made soon, the National Ballet is in danger of becoming an expensive irrelevance.