COCO CHANEL: NAZI SPY AND FASHION VISIONARY

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Spinning lies, cutting threads….

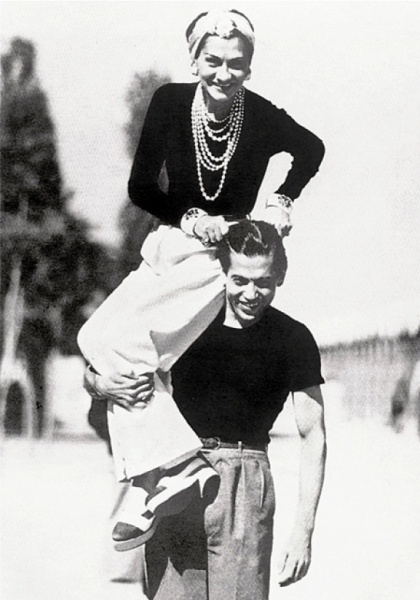

Coco Chanel was an original. She was also a bare-faced liar. Her deceits were like her thousand-dollar dresses: from bits and pieces of available material molded into fantastic creations. Like the clothes, the lies served to smooth over reality, cover up blemishes. They also helped make Chanel the first couturier to become a star. But at what price?

Lying her whole life, fleeing poverty and fearing rejection, she ended up rich, famous and utterly alone. She was a woman men loved but never married, a fierce independent whose career always came first. Her work was her refuge, what separated her from her impoverished siblings, whom she paid to disappear for fear they would alert the world to the truth about her past. Solitude, she would say toward the end of her life, was what was left once she finished reinventing herself.

Axel Madsen, who has also written biographies of Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, John Huston, Yves Saint Laurent and Sonia Delaunay, carefully knits together the complex pattern of Chanel’s complicated existence in his book, CHANEL: A Woman Of Her Own. It’s not an easy task.

Chanel constantly made up stories about herself, and Madsen has to separate fact from fiction. Where possible, he cites what Chanel said to other biographers (she never kept a journal or wrote many letters), juxtaposing her words with those of friends, colleagues, and journalists to come as close to the truth as possible. His writing is so intimate that Chanel’s life reads compellingly like a novel. Flaubert could not have invented a more intriguing character.

So who is this Emma Bovary of fashion? Born Gabrielle Chanel (the name that appears on her tombstone) in 1883 in a poorhouse in Saumur, a market town on the Loire River, she grew up behind the high walls at Aubazine, an orphanage run by Catholic nuns who taught her to sew. There were no mirrors at the orphanage to seduce a little girl with images of femininity. But there was yellow soap, clean white linen and astringent symbols of an austere life, one that Chanel would imitate in the uncluttered lines and pared-down details of her designs.

Life was sometimes messy. She had a series of rich and powerful lovers, the first being Etienne Balsan, who secured for her a botched abortion in the early twenties that later left her infertile for life. An English coal magnate, “Boy” Capel, followed, the only man she claimed to have ever truly loved. He was too ambitious to marry her, however, marrying a titled woman and keeping Chanel on the side. When the wealthy friend of Lloyd George died in an automobile accident on his way from Coco in Paris to his wife in Monte Carlo, something in Chanel died with him. She would never love again.

Yet more lovers followed: Igor Stravinsky, Pierre Reverdy, Paul Iribe, the Duke of Westminster and Hans Gunther von Dincklage, the Nazi she bedded during the German occupation of Paris. Chanel was eventually arrested as a result of this liaison; le Comité d’épuration, the “purging” committee of the Resistance movement that staged a series of public humiliations in the period following the German occupation, accused her of being a collaborator. Under duress, she remained her cool and haughty self. Photographer Cecil Beaton, remembering the scene, says that when asked if it were true she had consorted with a German, she flippantly replied, “Really, sir, a woman of my age cannot be expected to look at his passport if she has a chance of a lover.” She was 61.

Chanel walked after three hours when the British Foreign Office intervened, because she was in possession of secrets the British did not want revealed. She could easily have exposed the Windsors (Wallis Simpson had been a client) and others highly placed in society as Nazi collaborators, and shown that her fiend Winston Churchill had violated his own Trade With The Enemy Act. Once released, she moved to Switzerland and retired from couture for a decade.

Chanel used to hide in the back rooms instead of greeting the many rich and powerful clients who asked for her by name. In this way she created mystique. She had the foresight during the First World War to discern that women needed, no, wanted a new look. She trimmed away the crinolines, the pagoda hips and tapered lines of prewar fashion, and came up with a silhouette that was slimmer, younger, more liberated.

“To become skinny like Coco” was all the rage. Clients imitated her. They bobbed their hair like her, and bought her expensive dresses to look like her. Chanel made her look necessary. She used jersey and cotton, fabrics never used before in couture, and created a vogue for “dressing on a war income,” writes Madsen. “The orphanage . . . had taught her to improvise with bits and pieces, to find ideas in what was handy, to work with what was available. She understood that the war demanded a fashion of rummage, of salvage, a fashion that was simple and functional, and could be made up with opportunities and remnants.”

She became the symbol of the new woman. At the age of 32, she represented the future. People who would never have been found dead in the same social circles as their seamstresses now begged her to sit at their tables. She became part of a community that included Pablo Picasso, Misia Sert, Marcel Proust, Cole Porter, Somerset Maugham and Colette. Colette later wrote of Chanel: “By her obstinate energy, by the way she faces you and listens, by her guarded stance, which sometimes kind of blocks her face, Coco is a black bull.”

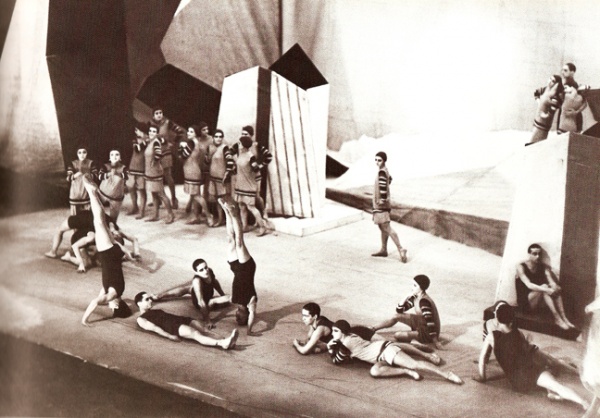

She could be generous to a fault, paying for Jean Cocteau’s detoxification cures, subsidizing Sergei Diaghilev’s ballets, making monthly stipends to Stravinsky and Reverdy, financing funerals, Diaghilev’s and Raymond Radiquet’s, Cocteau’s lover, included. Yet she was tight fisted when it came to her workers, compensating her models, on whom Chanel, who never sketched out her ideas first, created all her designs, 200 francs a month, or one-tenth of what she charged for a dress. Her staff staged a sit-down strike in 1936, which scandalized the elitist Chanel. When she recalled the event later, she showed no empathy: “What idiots those girls were.”

In 1953, Chanel staged a comeback that became the laughingstock of the season (the fashion press complained that she was stuck in a time-warp, circa 1930), and then the following year won over her critics with a wardrobe that was suddenly deemed timeless, elegant and perennially chic.

It’s this neo-classicism that has survived even Chanel’s lonely death in 1971 at the age of 88, becoming a staple of a revived House of Chanel under Karl Lagerfeld. Women around the world continue to mimic her look: the trim little suits in nubby wool, the ropes of faux jewelry, the two-toned shoes, the little black cocktail dress. They wear her perfume, Chanel No. 5, named after her lucky number, and believe they are embracing the legend herself. But it’s a folly.

“The modern career woman who has adopted her style as well- bred and safe is almost a caricature of Chanel the woman, who lived free and unconstrained, and loved a man too ambitious to marry her,” Madsen writes. skewering her imitators. She is, despite her flaws, unique. A woman of her own.