Fools Rush In

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Clowns are everywhere these days, appearing in leather and tattoos in the Franco-Swiss circus-for-grownups Que-Cir-Que, and adding a touch of the surreal to Quebec’s Cirque du Soleil. They inject zest into several new productions of Samuel Beckett’s vaudeville-inspired classic, Waiting for Godot, including the one that recently closed at The Grand in Calgary.

Earlier this year, Slava Polunin, a clown who once performed with Cirque du Soleil, toured his Slava’s Snowshow to sold-out houses around the globe. When he and his fellow clowns first blew into the Princess of Wales Theatre in Toronto nearly 20 years ago, audiences — and the critics — melted.

Variety gave it a big thumbs up, paving the way for the clown’s conquest of Broadway. When it opened on the Big White Way, clowning’s place in the firmament of current pop culture was confirmed.

“Putting clowns where they don’t belong, or where we don’t think of them as belonging, is a more recent phenomenon in theatre,” says Donald McManus, a Canadian drama professor and former clown who wrote his doctoral dissertation on clowns in 20th-century theatre.

“I think the clown’s main appeal is that it is clearly an anti natural image. It’s a way for theatre to turn away from straight representation, and yet still retain the human form. You still want to hear stories about people.”

McManus feels that clowns have, in fact, played a significant role in shaping modernist art of all forms.

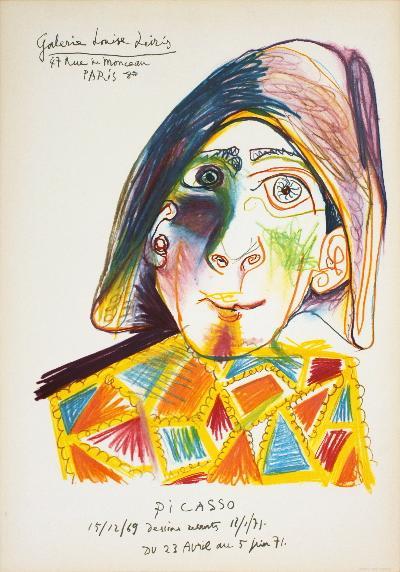

“When Picasso painted a recognizable figure it was often a clown. It’s a figure that represents the human but yet is clearly not human at the same time. So that’s its initial appeal. And also the modernists liked the fact that it was a low form. In other words, it was associated with popular forms of entertainment as opposed to what was going on in the salons.”

Ask the clowns themselves, however, and many of them prefer a social and political explanation for clowning’s popularity.

Richard Pochinko, the Canadian theatre guru who mentored many a Toronto clown before his death at 42 nine years ago, often told his students that in troubled times clowns come out in droves.

They were abundant during the two world wars and the Great Depression, difficult periods that spawned master clowns such as Charlie Chaplin, Buster Keaton and the white-faced Pierrot in Marcel Carne’s anti-Nazi film classic, Les enfants du paradis.

“I think that clowns are forever needed in our societies,” says Leah Cherniak, a Toronto director who has frequently put clowns in her shows.

“If we don’t have a clown to poke fun at our seriousness, we are in serious trouble. We need to laugh for all kinds of reasons. And we need to take that seriously.”