EDWARD HILLYER FLEW

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

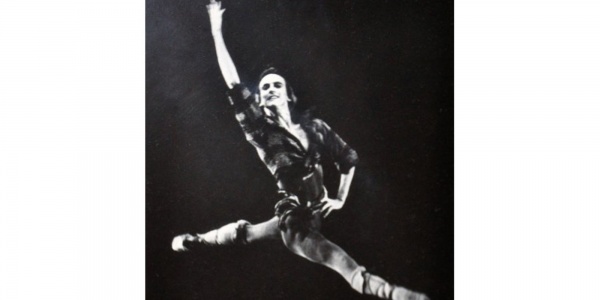

Former Les Grands Ballets Canadiens principal dancer Edward Hillyer passed away suddenly in his Montreal apartment in 2017. He was just 59. Few in Canada seemed to notice — let alone mourn — his passing. Only Dance Magazine in New York ran an obituary, saying this about his many achievements: “Known for his dramatic, dynamic style, rigorous work ethic and command of both classical and neoclassic styles, Hillyer was a sought-after soloist with major companies, including the Hamburg Ballet and New York’s Lar Lubovitch Dance Company from the late ’70s through the ’80s. He was proclaimed Canada’s “dancer of the year” in 1982.”

Born in Alameda, California, Edward had trained at the San Francisco Ballet School and the National Academy of Arts before coming to Canada to dance in the early 1980s. He choreographed too, for opera and film as well as the stage. Works like Pour Brad, his 1983 choreographic tribute to his late brother, Epreuve de Force, Reach of Children, De Profundis and Descente de Croix, the 1989 ballet which won him Canada’s Clifford E. Lee Choreography Award, stood out for their rich musicality, clarity and precision of line.

After he quit performing, Edward became a highly regarded master teacher with Les Grands Ballets Canadiens. He also served as a guest ballet master with the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, the National Ballet of Canada, Nederlands Dans Theater, Ballet, the Beijing Ballet and Ballet Philippines.

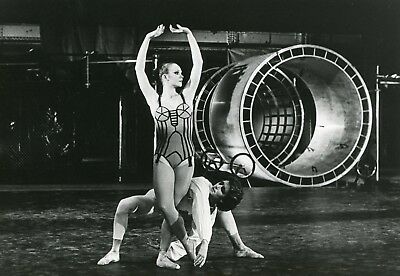

La Salle de pas perdus, a new James Kudelka ballet created as a follow-up to his 1984 work Alliances, had its world premiere before a small and indifferent crowd at Place des Arts on Thursday night. As the first work that Kudelka has created for Les Grands Ballets Canadiens since last year’s unorthodox retelling of Stravinsky’s Le Sacre du Printemps, La Salle des pas perdus stands as a disappointing chapter in the otherwise bright history of this promising young choreographer.

Les Grands Ballets Canadiens, now celebrating its 30th anniversary season, commissioned this ballet to fit into its Brahms evening, which was also the first evening dedicated to works of the company’s resident choreographer. Like Alliances, also featured on Thursday’s program, La Salle des pas perdus follows the four-part structure of a Brahms piano concerto. Alliances is set to Piano Concerto No. 1; La Salle des pas perdus to Piano Concerto No. 2. In strong command of both was pianist Rolf Bertsch, who played with the orchestra of Les Grands Ballets under the baton of musical director Vladimir Jelinek.

Brahms’ music is classical in form, romantic in temperament, and charged with an emotion that does not lend itself easily to narrative interpretation. For a choreographer, tackling Brahms is a little like trying to take treasure from a sleeping giant – you have to grab the gold and avoid being crushed.

In Kudelka’s case, Brahms is a force too big to tackle.

In both works, Kudelka fails to wrest control from the music, allowing it to dominate him in mood, tone and structure. In both works, he appears to follow Brahms slavishly, creating gestures that lack emotional depth of their own. Without inspiration, the choreography has the dull allure of a flattened piece of tin.

Kudelka tries to cover the dross by dressing up La Salle des pas perdus in the richly embroidered robes and natty, peacock blue military jackets of La Belle Epoque. The costume designs, one of the most striking features of the work, are by Santo Loquasto, an Oscar nominee for his designs in Woody Allen’s Radio Days. Loquasto last worked with Kudelka when the choreographer created Heart of the Matter for New York’s Joffrey Ballet in 1986.

The ballet’s design seems less indebted to Brahms and more to Poems of Peace and War by French poet Guillaume Apollinaire, a passage of which appears in the program notes. Claude Girard’s sets range from the interior of a train station (loosely translated, La Salle des pas perdus is the waiting room of a train station), to a high-tech metal shelter, to an open field beneath the stars. The final scene features something resembling a arched trellis, beneath which the reunited couple meet and dance.

As in Alliances, the transitions from one scene to the next are awkward and leaden. With the exception of the finales in both works, each scene comes across as a self-enclosed unit of expression that contributes relatively little to a sense of the work as a whole. As the parts fail to build on each other, the work loses steam early in the game.

The ragged performances in La Salle des pas perdus may be a result of the work’s dire need of direction. None of the approximately 25 featured dancers seem willing to fuel the choreography with emotion or dramatic impulse. But it seems more likely that this spotty crew was under- rehearsed or, equally, that it was just not up to meeting the challenge of Kudelka’s difficult steps: arms beat the air without precision or finesse, ankles wobbled and backsides came perilously close to the ground too often for anyone to turn a blind eye.

One of the few inspired performances was given by principal dancer Edward Hillyer in Alliances. In a ballet punctuated by gentle lifts and bold leaps, Hillyer danced head and shoulders above the rest. A performer of buoyancy, grace and great spirit, Hillyer lent grandeur to ballet that otherwise lacked conviction.