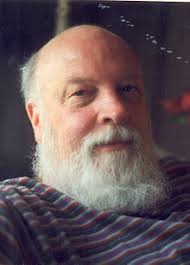

REWIND– CULT DIRECTOR PAUL BARTEL

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Did success spoil Paul Bartel? Well, yes and no.

To illustrate, let’s zoom in for a moment on the life and times of the director best known for his films Eating Raoul, Death Race 2000 and other social satires that the American-born auteur made far from the Hollywood studio system before his untimely death in 2000, at age 62. Ready. Quiet. Action

Close-up of Paul loving Raoul: Over lunch in a downtown Toronto hotel restaurant where the waiters in celebration of “ethnic eating day” sport name tags proclaiming their place of origin (Hi! My Name’s Habib. I’m From Egypt!), Bartel is pleasantly surprised when asked by an approaching fan if he would autograph a poster advertising Eating Raoul, the 1981 film satirizing the cannibalizing habits of America’s urbane middle class. “I’d be delighted,” the portly director beams. (Habib gives him a Coke for free.)

Three-quarter shot of Paul resenting Raoul: Taking thoughtful sips from his glass of Coke, Bartel says the price of celebrity is this: His latest film, Shelf Life, made in 1995, had its opening delayed for more than a year because distributors were miffed that it was not Eating Raoul, or anything like his other eight movies. In short, they said it was not a Bartel flick at all, a sentiment shared by the organizers of the Sundance and Toronto International film festivals, who, by rejecting Shelf Life, almost buried it forever.

A screen adaptation of a strange but intimate play about three Kennedy- era siblings who live 30 years underground in their parents’ bomb shelter, Shelf Life is a parody of “nuclear” family values and pop culture attitudes. The 83-minute film marks a departure for Bartel because, for one thing, he didn’t script it himself. He saw the play, written by actors Andrea Stein, O-Lan Jones and Jim Turner to showcase their highly eccentric performing style, in Los Angeles, where he now lives (he’s a native of Brooklyn). He was instantly smitten.

It was a small enough project to be made independently – that is, with $500,000 (U.S.), of which $350,000 was his own money – but he was also intrigued, he says, by the comic energy of the performers, the resonance of their ideas about American culture, about relations between men and women and about how restricting physical realities can be opened up by the strength of the imagination.

But once finished, Shelf Life was, well . . . shelved. “The greatest problem about getting this film released has been because of my earlier work,” bemoans Bartel. “People expect Eating Raoul or Not for Publication. They are surprised when they see it, even confused. Even though it has something in common with my other films in that it’s also about unconventional subjects. But the style is so completely different and that’s what throws people.”

Pull-away of Paul wishing Raoul would retire: “A producer sent me a play the other day that he wants made into a film,” Bartel says. “It’s a about a woman who is raped by a friend of her uncle and in the second act she gets revenge by serving them a meal, the remains of the aborted fetus.” (The Egyptian sunlight fades quickly from the face of an eavesdropping Habib.) “It was quite well written,” Bartel continues without pause. “But I realized while reading it that the producer thought of me only because of that moment of cannibalism. And I thought, oh God, I’ve become typed as the cannibal director.”

Cut to Paul in another place and time: There are other things you could call Bartel, not all of them having to do with flesh-eating wannabes from the suburbs. Angry young man, for instance. “I think I got involved making films about society and especially about problems in society because I used to be a pretty angry guy,” confides the director, graduate of UCLA’s film school and Rome’s Centro Sperimentale di Cinematografia and sometime actor in films like Rock ‘n’ Roll High School and Amazon Woman.

“I am gay,” he continues. “And I think that being gay has been the biggest source of conflict in my life. And growing up in the 1950s it was taboo to be gay. I don’t think it was easy for my parents. But I also had a sense at the time that my parents had misrepresented society to me, and also other passions which they didn’t approve of or didn’t allude to and didn’t condone. As I grew up I came to terms with that, and with my parents, and more importantly with myself.”

Bartel has addressed his gay identity in some of his films, Scenes From the Class Struggle in Beverly Hills, for instance, and also in a new script he is writing tentatively called Modern Marriage. “It’s about two guys who are roommates, one’s gay and one’s straight, and both are about to enter a long-term relationship with another person though each has a problem with commitment. It’s more straight, if you’ll pardon the pun, in that I’m not looking to criticize here, but rather to show how people can be brought together. I will do this by minimizing differences instead of exacerbating them.”

Fade on Paul as eternal optimist: “I’ve always been more interested in doing my own eccentric little films instead of being a studio director,” relates the one-time apprentice of Roger Corman (The Wild Angels, The Trip ), and mentor to Martin Scorsese, Francis Ford Coppola and Peter Bogdanovich. Bartel says he likes to have control over his work. If it’s bad (like the ill-reputed Lust in the Dust, a western parody starring Divine) then the responsibility’s all his. If it’s good, then pride will prevail. “Despite the rejection at a number of festivals, I believe in this film,” Bartel offers. “I know it really works.” (Habib smiles.)