SATIN IS IN THE DETAILS: THE ENDURING MYSTIQUE OF MEDIEVAL THEATRE

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

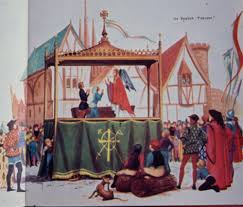

A Saturday in May, the first day of the Towneley Cycle. The sun is shining, the sky is blue. Mothers are suckling their babies, lovers are peeling oranges, scholars are scribbling notes. A fanfare cuts through the sultry air. God has just sat gingerly upon his throne. The world’s about to begin. With a flick of the wrist, He unfolds the heavens, the waters and the plants of this earth. With a bellow of His kingly voice, He awakens the sleepy animals and creates Man and Woman.

In the audience, a small boy is staring, his mouth full of buttered roll. Satan slithers onto the stage in the guise of a snake. The boy stops chewing. He can’t believe his eyes. He stands up and walks until he’s an arm’s length away from the action. “Don’t do it,” he cries. “Don’t eat the apple!”

IT WASN’T quite an office, though well stocked with technical toys: a wall of filing cabinets, an electric typewriter, an answering machine (with friendly message). It was more like the morality department of some godforsaken museum. In one corner, a devil’s head; in another, the brazen sword of the archangel Gabriel. On the wall, an empty bag of potato chips labelled “Cain’s.” Here endeth paradise.

This tiny room in the basement of the University of Toronto’s Centre For Medieval Studies is (or used to be) the sometime home, sometime think-tank of the late David Parry, academic, actor and former artistic director of U of T’s medieval theatre group, Poculi Ludique Societas (loosely translated: Society of Revels and Games), who passed away in 1995, at the age of age of 53. Founded in 1965 and and devoted to rediscovering the theatrical traditions of the Middle Ages and the Renaissance through research and dramatic experimentation, the PLS’s present artistic director is Linda Phillips.

This was where Parry wrote scholarly papers, practiced his lines and organized playing dates for his acting troupe. And where he arranged traditional songs to be his many albums. It’s also where he peddled video tapes of PLS (also known as The President’s Players) performing a varied stock of mostly pre-Shakespearean English drama as teaching aids for other university groups interested in his type of theatre. He had made an art of it.

On a particular morning in the not so ancient past, Parry was on the phone with an academic from Connecticut. He was trying to sell him a two-hour taped version of the Toronto Passion Play. Cost $525. Or, how about Robin Hood and the Friar? A bargain at $230. Wait, a special. A tape of the Killing of Abel for $400. Only seen once. That was when the PLS performed it as part of the Towneley Cycle as part of a two-day medieval theatre festival on the grounds of U of T’s Victoria University. The deal was almost in the bag. Parry hung up, a little breathless, but pleased, and said in a lilting English accent, “He can’t make up his mind. He’s got about $1,100 U.S. to spend. He’ll call back.”

He did call back because Parry made medieval drama roar with laughter and howl with real tears. He gave it back its spectacular larger-than- life status without forgetting to brush a light finger over the blushing cheek of a maiden in love, or the furrowed brow of a child afraid of the dark. He called back because Parry’s updating of the fifteenth- century Towneley Cycle remains an engrossing piece of theatre, not to mention a mind-snapping work of scholarship. The Towneley Cycle presents many challenges.

Unlike other collections of biblical plays – such as the York and Chester cycles – the Towneley is not firmly attached to a town or city. But scholars have come to associate it with the town of Wakefield in the West Riding of Yorkshire because of two clear ascriptions to the town found in the remaining text: one at the beginning of the Creation play and one at the beginning of Noah.

According to Parry, no other evidence exists to suggest that the other plays in the cycle belong to Wakefield. “The evidence that it is a complete cycle at all is very slight,” he said reclining in a chair with arms across his chest in true professorial fashion. “At least five plays have been borrowed from York to give Towneley the appearance of a cycle, and about five or six more were written by someone we call the Wakefield Master to fill in the gaps. But, there are still sections missing. One of my tasks was to write new bits to complete the play.”

Parry did this by trying to get inside the head of the enigmatic Wakefield Master to mimic his style and his tone of voice which, says Parry, grates with a “savage sense of social satire and a bleak view of the world’s corruption.” Parry worked largely from original accounts of stories featured in the cycle – the Book of Genesis and sections from the Apocrypha. He spent most of his time figuring out how the Bible could be conceived as stage action and how he could render the existing cycle into modern English. Often, he felt as though he were performing a high-wire act: “A lot of the time it was a choice between academic purity and theatrical necessity.”

The trick, of course, was balancing all the available material for a production that, in Parry’s words, “succeeded as scholarly research, entertainment and community event.”At the end of the two-day medieval theatre festival, Parry presented an academic paper on his treatment of the text.

Parry was a bit of an old hand when it comes to revising medieval plays. He claimed that even as an undergraduate in his native Hull in Yorkshire, he was always interested in reworking early morality plays. After he did his master’s degree in medieval drama at the University of Victoria in British Columbia, he came to Toronto in hopes of doing a doctorate on a comparative study of classical Indian drama and medieval theatre. But the topic was too large, “too long-lifish,” said Parry, to get off the ground.

He got his academic break in 1979 when he did a production of The Castle of Perseverence, a big-scale morality play from the early fourteenth century, on the U of T campus. It worked so well that John Leyerle, the late U of T professor whose 1964-65 graduate seminar in medieval drama inspired the formation of PLS (originally from Professor Leyerle’s Seminar), suggested to Parry that he do a new edition of the play. The result was a doctoral thesis entitled, A New Critical Edition of the Castle of Perseverence. It was published in 1999.

Soon after, Parry also released The Wind That Tramps The World, and album featuring traditional folk songs and stories from Britain and Canada. The project built on his work with the PLS. “The whole thing is a form of story-telling, whether with mime or song,” Parry said at the time.”You’re always trying to draw others on the outside inside what you’re telling.”

Whether singing, acting or directing, Parry was always trying to re-establish some cultural roots connected “in some real way with that huge reservoir of tradition that covers everything from epic to comic stories that have ways of tuning us into what life’s all about.”

He was quick to add, though, that his revival of story-telling and medieval drama isn’t really being done for the sake of converting thousands of Blue Jays fans to follow wandering minstrels and eloquent devils, his idea of popular entertainment.

“I’m not doing all this as a crusade. I do it because I enjoy it and because I think it works. The more people see and hear [traditional forms of theatre], the more they can enjoy it as an alternative to canned media. It will always have a limited appeal, but to a lot of people who haven’t experienced it before, it comes across as unmistakably fresh and exciting.”