HE PAVED THE WAY — ARTHUR MITCHELL

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Arthur Mitchell, the African-American ballet dancer who danced for New York City Ballet and went to found the ground-breaking Dance Theatre of Harlem, has died at the age of 84. He was a legend in his own time and I once had the great privilege of sitting down with him for a prolonged conversation about his life and work. I share that 1995 story here in tribute to the dancer who broke down so many barriers in ballet:

HE threw out his dancing shoes years ago, when the body first began showing the wear and tear of years at the top of George Balanchine’s New York City Ballet. But he never got rid of the passion for dance that, as a kid, took him off the streets and into the mirrored rooms of classical dance.

“Dance is life,” booms Arthur Mitchell, artistic director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem which comes to Toronto’s O’Keefe Centre tonight through Friday, as part of a five-city North American tour that opened in Ottawa last week. “It’s that simple. Many ask me what is the first art form and I say it’s dance. Dance is movement and that’s what we do in the womb before we’re even born when we’re kicking and stretching to make ourselves known.”

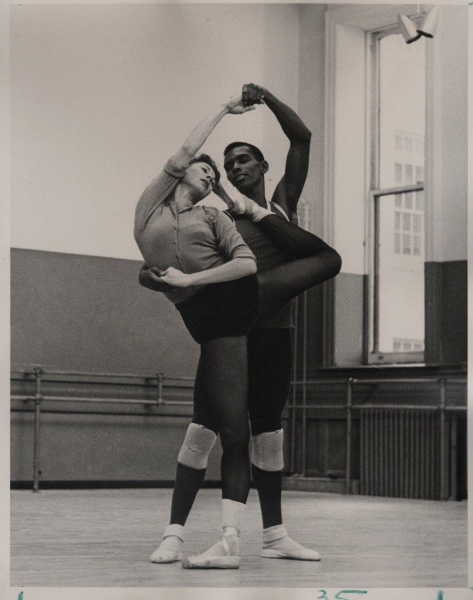

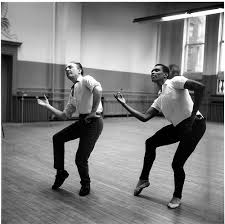

One of the most celebrated ballet dancers of this century, Mitchell became the first black male dancer to become a permanent member of a major dance troupe (New York City Ballet) in 1956. Then, after quitting the stage in 1968, he went on to found the Dance Theatre of Harlem.

Mitchell’s entree into the world of dance occurred in the late 1940s when an eagle-eyed teacher in high school spotted him jitterbugging at a class party. The teacher urged him to audition for a place in New York’s famed High School for the Performing Arts, the setting for the movie Fame. He succeeded and began to train in jazz, modern and tap dancing. He didn’t take up ballet until he was 18 – a late start in that most professionals begin classical dance before the age of 10. But his determination paid off with an entrance scholarship to the School of the American Ballet, the prime “feeder” of dancers to the New York City Ballet. After joining the NYCB, Mitchell became one of its most popular soloists, assuming roles in many Balanchine ballets including Agon (1967) and A Midsummer Night’s Dream (1962). Mitchell next week will be given a Lifetime Achievement Award from the School of American Ballet. Only three others have been so honoured: the late Rudolf Nureyev, choreographer Jerome Robbins and ballerina Alexandra Danilova. Not bad company.

“It makes me feel very sage,” offers Mitchell. “Though, really, I don’t think in those terms because I still have so much to do.”

When he talks he moves his hands in imitation of wave-like patterns or else sharp diagonals, visual reminders of the lines of movement that have shaped his life. At age 60 his body is still lean and sinewy. He sits tall and proud, dressed this day in a blue suit, crisp white shirt and red tie. It seems more a corporate uniform than a dancer’s outfit, but then Mitchell has always been interested in breaking preconceptions and eliminating barriers.

“There’s a fallacy that dancers’ brains are in their feet,” he chortles. “I’d like to show that we can be good businessmen, good administrators, that we’re articulate and can get things done.”

Before him on the table is a leather-bound agenda, meticulously filled in with pencil markings. These reflect the schedule of a man who not only directs the Dance Theatre of Harlem but who also runs the school of the same name up on West 152nd Street in Manhattan.

He originally founded the school as a means of getting black youngsters off the streets. But as the company that depends on the school for some of its dancers raised its standards, the school had to begin concentrating more on children with talent. At the same time, Mitchell says he would never deny a young person exposure to dance within his school, or his company, and he continues to hold open-door auditions on Saturdays.

“The arts are what changed my life around. They gave me a sense of self-esteem, of discipline and of focus. That’s why I’m adamant that young people have the arts in their lives because that’s where self-esteem and pride come from.”

Each year more than 1,300 students, ranging in age from 3 to 21, pass through the Harlem school, attending eight-week semesters in the fall and spring and six-week sessions in summer. For those who don’t, finally, make it as dancers, Mitchell hopes they gain enough in discipline and self- esteem that they enjoy successful careers in other fields.

“People have said to me, hey, but you’re exceptional. We can’t be like you. But I say to them, no, I’m not exceptional, I just had the opportunity and I took it.”

What made Mitchell’s opportunity particularly special was the chance to work with genius. Balanchine was his teacher, choreographer and mentor. Composer Igor Stravinsky, who worked with Balanchine in creating a number of neo-classical ballets for NYCB, including Agon, also influenced the young Mitchell. Another influence was Karel Shook, a former teacher at the School of American Ballet who helped Mitchell found the Dance Theatre of Harlem in 1969.

DTH, which gave its first performances in 1971, was started partly in response to the assassination, in 1968, of Martin Luther King, Jr. King, says Mitchell, inspired his belief that American blacks needed their own ballet company to grow in an art form whose highest expression is the ballet blanc. Over the years, DTH has evolved into a multiracial company which, nevertheless, tends to focus on ballets with identifiable African- American themes. The program the company is bringing to Toronto features Alvin Ailey’s The River, a ballet influenced by black gospel music; Geoffrey Holder’s Dougla, a work inspired by a Trinidadian marriage ritual; and John Taras’ Firebird, a remake of the famed Balanchine- Stravinsky collaboration of 1949 that unfolds on a mythical Caribbean island. Also on the programs are Michael Smuin’s Medea, based on the ancient Greek myth, and Ron Cunningham’s Etosha, inspired by the sight of animals in Africa drinking at a waterhole.

“I didn’t start out dancing at a young age, so ballet was never that easy for me,” Mitchell notes. “I worked for everything I ever had. But the love of the art form was always there; I saw the technique as a means to an end – to free yourself to dance. I tell my dancers today, when they ask me how I did it, not to be classical, but to be classic. If you’re classical that’s an affectation. But if you’re a classic then you can last an eternity.”