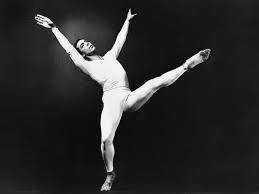

LAST DANCE: REMEMBERING PAUL TAYLOR

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Today’s sad announcement of the passing of American modern dance pioneer Paul Taylor at the age of 88 has prompted me to recall the time I spent in his engaging company in New York when he was still very much in his prime. We met initially at his home to talk about dance in general and his own Paul Taylor Dance Company in particular. Later that morning, he walked me to his studio to watch a rehearsal where I remember looking in awe upon the sinewy presence of Christoper Gillis, Montreal dancer Margie Gillis’ brother, who was a company member at the time. He would die of complications from AIDS some eight years later. Taylor had influenced a great number of dancers around the world, including others with Canadian connections. They included Danny Grossman who took what he learned from Taylor — abstract gestures supporting realistic story lines — when he created his Danny Grossman Dance Company in Toronto in the 1970s. I would stay in touch with Taylor on and off over the years, writing about him as recently as this past February. I remained a fan of his work. I remember another time when we met, backstage at New York’s City Center following the world premiere of his 1988 work, Speaking in Tongues. He had set what would become one of his most critically acclaimed pieces to a score by an unknown Canadian composer — Winnipeg’s Matthew Patton — after receiving the unsolicited tape through the mail. Broadcast on PBS in 1992, Speaking in Tongues, a sharp-edged critique of U.S.-style evangelism, would go on to win an Emmy for outstanding choreography. I am relieved to say I recognized its greatness from the start. I gave it a great review. And that really was because I considered Taylor a genius. But an approachable one. He did not occupy the dance equivalent of the ivory tower. His dances spoke to directly to you. They moved you and made you think. As a person and as a choreographer, I found him to be as generous as he was insightful and richly inventive. A true artist and gentleman, he impacted the course of modern dance in his lifetime. I am honoured to have known him, even briefly. Here is that first interview I did with him in 1985. I think it captures Paul Taylor in his element.

PAUL TAYLOR, looking more like a model for Ralph Lauren than one of the founding fathers of American dance, shuffles to the door of his New York townhouse in sneakers and jeans and calls to his dog, D.D. (“it’s short for damned dog,” smiles Taylor) to come upstairs.

D.D., a mangy old thing that has been Taylor’s constant companion for 15 years, humbly obliges and when she hobbles into the room, looking hurt and happy at the same time, Taylor pats her behind the ears and explains how D.D. is more than a friend, she’s the symbol for his life’s work.

“There are two basic breeds of dog,” he says, slinging one long leg over the other. “Wolf or jackal. And this here is a jackal dog. Though she’s a mongrel, she’s also a classic and that’s how I think about my own work.”

What prompts Taylor to wax poetic over his ancient dog is a consideration of his work as being distinctly American. Anyone who sees his dances can tell that they were born in the USA. The dances come from a mixed heritage, yet have a distinctive American flavor. Taylor, who was born in Alleghany County, Pa., in 1930, says he can’t quite put his finger on it. But, “I am very American and so whatever I make would have to be, too.”

Tonight, when Taylor’s company (this year celebrating its 31st anniversary) opens a six-night run at Toronto’s Premiere Dance Theatre, Canadian audiences will be able to judge for themselves what makes Taylor’s work so baldly American.

Some may focus on the technique which is heavily influenced by Martha Graham, Taylor’s former teacher – “she was a strong influence on my own dancing life.” Others, however, may fix on the broad and eclectic range of ideas.

Taylor, who was an athlete before he was a dancer and a modest painter before he was a choreographer, brings a variety of experience to his work. But if you try to pin him down to an explanation of how his experiences actually mold his dances, he claims he doesn’t know.

“Where the ideas come from is very mysterious. We don’t really know much about the creative process. But I think that a lot of choreographers would agree that blood memory has something to do with it and a certain familiarity about the ways bodies move.”

Taylor also believes that you can’t teach someone to be a choreographer, but you can teach them craft: “there are endless possibilities of making dances. You can draw on certain forms, trace architecture, create steps. But why one step seems better than the other is difficult to know.”

It’s also difficult to talk about. Trying to get Taylor to describe his dances is like trying to wrestle information from a Freemason.

He doesn’t quite refuse to answer questions about them, rather his answers are vague and inconclusive. It seems his work is a highly personal, even private experience. Yet he maintains that his work is not about him – “they’re meant to be the dancers on the stage, whatever the subject.”

Taylor is not a choreographer who sets out to imitate life. “I don’t think that dance is a realistic form and in my work there’s never an attempt to put realism on the stage.” When he makes dances, he aims to build on the dancers in his own company, though he says he it’s not their personalities which inspire – it’s their bodies.

“But still I hesitate to use the word ‘abstract’ when talking about my dances,” he says, shifting his hefty frame in his chair. “I find it difficult to look at a person dancing and think in abstract terms.”

However, some of the works performed in Toronto may come across as abstract. One of his dances from last year, . . . Byzantium, “has no story and no moral.” Based on Yeats’ poem of the same name (the three dots are what remains of a borrowed line), the dance is meant to “make some comparison between religion, or the lack of it now.”

Last Look, a new work, is described by Taylor as “very ugly – it’s ungraceful and it has a meaning and feeling that is not what many think of as pleasant.” Roses, another new work, strikes a different note. “It’s old-fashioned – a dance for couples.”

Diggity, a work created in 1978, is one Taylor’s favorites, largely because it involves a set featuring dogs, hundreds of them littered across the stage “like an obstacle course.” Why dogs? “They have dreams, too.”