Elusively Fluid-Farewell Trisha Brown

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

American postmodern dance pioneer Trisha Brown has died in New York, the city where she reinventing dance as an act of non-virtuosic rebellion. She was legendary, even in her own time, and in 1989 I went to New York to review her latest premiere, a collaboration with the artist Robert Rauschenberg, a frequent collaborator. Reading my Globe and Mail dance review, I can see her again vividly in memory, her hips swaying sensuously as she danced as she often did– with her back to the audience. I hope it recalls to you, too, how unique she was:

American postmodern dance pioneer Trisha Brown has died in New York, the city where she reinventing dance as an act of non-virtuosic rebellion. She was legendary, even in her own time, and in 1989 I went to New York to review her latest premiere, a collaboration with the artist Robert Rauschenberg, a frequent collaborator. Reading my Globe and Mail dance review, I can see her again vividly in memory, her hips swaying sensuously as she danced as she often did– with her back to the audience. I hope it recalls to you, too, how unique she was:

Choreographer pushes limits of unpredictability

DEIRDRE KELLY

25 March 1989

NEW YORK

WITH Astral Convertible, U.S. modern dance innovator Trisha Brown forges a meeting ground for old and new. Where in the past the 52-year-old dancer and choreographer explored the rock-bottom elements of dance – space, time and weight – and the ways in which external influences affected them, today she is concerned with seeing how the basics of choreography affect and (significantly) alter the world around them. The new piece, which had its U.S. premiere at City Center last week, excites and startles precisely because of this unpredictability.

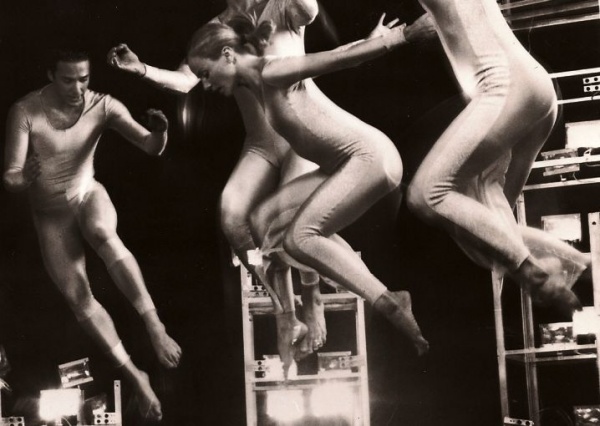

As she has done many times in the past, Brown has here collaborated with artist Robert Rauschenberg. He designed the sets, a series of eight aluminum towers with headlights attached, while Richard Landry, another long-time collaborator, designed the sound: traffic noises mixed with instrumental and percussive compositions. The sound system and Ken Tabachnick’s lighting designs are hooked up to sensors hidden within the Rauschenberg towers. They respond to and are directed by the dancers’ changing movement with the result that it is the choreography that determines the aural and visual composition and not the other way round.

Brown introduces a wide margin for controlled improvisation, which means that no two performances of the piece are the same. A hand gesture one night might sound a drumbeat, raise the volume of the city traffic. On another evening, the same hand might move differently and inspire a whole new set of noises or lighting effects. It is unpredictable, yet in many ways reminiscent of Brown’s avant-garde work in the past.

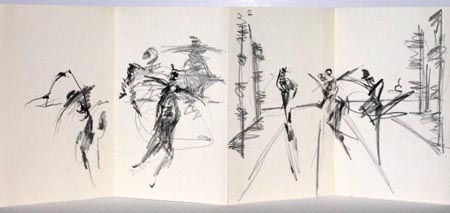

In the sixties, when Brown was cutting her teeth on experimental work, she specialized in artful collaborations with artists from other disciplines. From the beginning, she was interested in widening the parameters of dance and jostling conventional ways of seeing movement in the theatre. She specialized in “happenings,” events organized around a “found” object or chance occurrence. Astral Convertible harkens back to those days with its concentration on randomness of expression and serendipity of design.

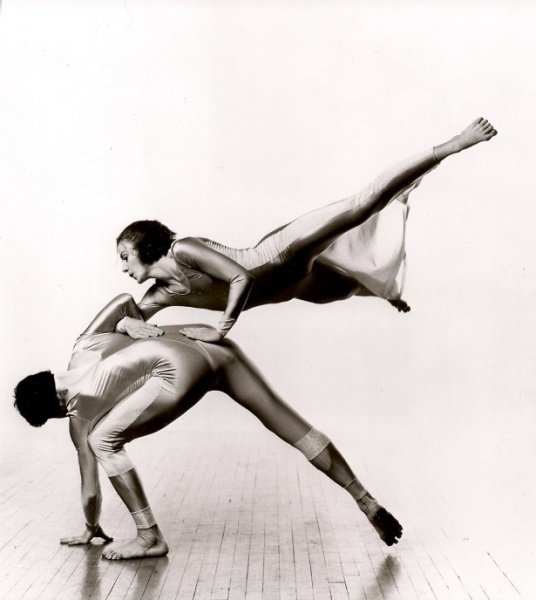

Critics have noted that, on one level, Astral Convertible is sixties avant-garde recycled for eighties sensibilities. The brooding, post- industrial aura of the entire piece and the varying nature of the work’s formal elements do lend themselves to this interpretation. But with this work Brown reaches some kind of breakthrough in technique. While it is true that Astral Convertible is set in the context of previous works – familiar are the volubility and propulsive flow of movement, the careful spacing, sudden changes of speed and constant shifts in spatial relationships – the dancing is looser, the phrasing more dynamically varied and the rhythms more keenly edged. The dynamism alone is stunning, as are the shapes the dancers carve out of their loose-limbed and precisely angled bodies.

Astral Convertible was originally commissioned by the Montpellier International Dance Festival and co-produced with the Aix-en-Provence International Dance Festival, both in France. It received preview performances in Moscow last month as part of the Rauschenberg Overseas Cultural Exchange, and will have its open-air premiere in Montpellier in June.

Brown presented it on a mixed program consisting of works from the past, including Set and Reset, her now classic 1983 collaboration with Rauschenberg and Laurie Anderson, and Opal Loop, a work danced in silence.

Alternating with this program at City Center was another also featuring past works: last season’s Newark (Niweweorce), with a set and sound concept by sculptor Donald Judd; 1985’s Lateral Pass, with sculptural pieces designed by Nancy Graves and a score by Peter Zummo, and 1981’s Son of Gone Fishin’, designed again by Judd with a score by Robert Ashley.

Brown danced a solo in Lateral Pass, and while she is perhaps a generation older than the nine nubile dancers now in her Trisha Brown Company, she amply suggested the zest, intricacy and loose-hipped sensuality of her salad days. Lateral Pass illustrates Brown’s distinctive style and technique, as it is formed of “accumulations:” small, plain moves collected in what critic Deborah Jowitt has called an “add-a-gesture structure.” Each piece of movement is like a building block on top of which Brown supports dances of increasing richness and complexity. Brown’s dances, like Brown’s dancing, are expressions of elusive fluidity, and anyone interested in virtuosity and integrity in choreography shouldn’t miss them.