The Gould Rush: Glenn Gould Still Draws a Crowd

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Alessandro Columbo is serenely confident behind the wheel of his rented Chrysler Neon, coursing smoothly through the streets of Toronto like a local. He even handles the squeegee kids expertly, not bridling at what to him is a strange and uniquely North American phenomenon, but giving them just the right amount of eye contact and an inoffensive wave of the hand before driving off.

An architect from Milan, he has been in the city for less than a week, but already he is more familiar with the cultural landscape than most residents. True, he didn’t visit the Royal Ontario Museum, only looked at the CN Tower and refused to go into the SkyDome because of its monstrously ugly design (remember, he’s an Italian). But he has seen almost every landmark in town with a connection to Glenn Gould.

The late great Canadian pianist, who would have turned 84 today, September 25, is the sole reason Columbo has come to Toronto. And he’s not the only one to make the journey for Gould. John Miller, administrator of the Glenn Gould Foundation in Toronto, estimates that hundreds tourists each year come specifically to seek out “Glenn Gould” places, from the house in the Beaches, where he grew up, to Massey Hall at the corner of Victoria and Shuter streets, where at age 13, Gould made his orchestra debut to an astonished audience. His grave in Mount Pleasant cemetery, Miller says, is the most visited in Canada.

But don’t call them Glenn Gould tourists: For them, honouring the life and music of the pianist is not a busman’s holiday but a pilgrimage on sacred ground. “To listen to Glenn Gould’s music is a very rich experience,” said Columbo, driving with quiet purpose to Gould’s grave. “He gives us music and ideas and emotions. He is not only important as a musician but as an intellect.”

At the main gates of the cemetery there was no map to guide him to the site. But as if on cue, a passing groundskeeper stopped to give directions. Clive Haigh has worked at Mount Pleasant for 18 years and he is used to guiding people, mostly foreigners, to Gould’s piano-shaped marker.

Columbo asked if there are other famous Canadians in the cemetery. “Oh yeah,” said Haigh, “Foster Hewitt and Punch Imlach.” Columbo looked confused until he was told they were hockey personalities. “Oh yes, now I understand,” he said with a shrug. “A hockey player has to be more important than a pianist.”

Maybe so. But 34 years after his untimely death at age 50 on Oct. 4, 1982, Gould’s popularity has never been greater. Sony has just released a new multi-CD compilation, Glenn Gould Edition;a new biography has been published, Glenn Gould: The Ecstasy and Tragedy of Genius, by psychiatrist and long-time Gould friend Peter Ostwald;the Royal Conservatory of Music has recently renamed its professional training school the Glenn Gould Professional School; and author Tim Wynne-Jones has published The Maestro,a children’s book with a Gould-like figure at its heart.

So far, there is no organized Glenn Gould tour in Toronto, no Glenn Gould boutique. Those who want to make the pilgrimage need to do their research beforehand, consulting the plethora of Gould Web sites, for instance, or reading Ostwald’s biography, published in time for what would have been the artist’s birthday on Sept. 25.

One who frequently makes the journey to Toronto in honour of that birthday is Rebecca Rutkowski, a musician from California. Rutkowski wanders the Inn on the Park, the hotel where Gould occupied rooms from the sixties until his death. She eats where he ate and, although she can’t sleep in what used to be his bed (shortly after he died his rooms were converted into storage), she spends much of her time cloistered in the hotel playing her violin like a song of love.

Reached at her home near Los Angeles, Rutkowski spoke passionately of her devotion: “You almost feel like you’d like to say prayers to God so that there’s always light and golden colours around him.”

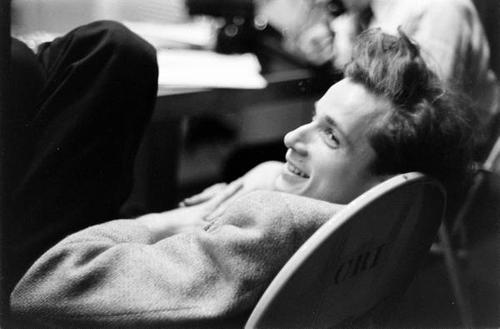

Gould is the phantom lover to many a devotee, male and female alike. His sexual ambiguity (no one is really sure what his sexual orientation, if any, was), his brooding good looks, his flamboyant eccentricity (the hotel concierge recalls him lounging by the pool, in the middle of July, dressed in mittens, coat, hat, scarf and galoshes) and his unmistakable genius for playing the piano have created a mystique that is as erotic as it is intellectually engrossing.

Canadian director Francois Girard added to the mystique with his 1993 film, Thirty-Two Short Films About Glenn Gould. Ditto for Switzerland’s Du magazine, which devoted its entire April, 1990 issue to the artist, calling it Mythos Glenn Gould. But it was the late Austrian author Thomas Bernhard who was the first to scale the mythological heights of Gould’s posthumous reputation and to point out the mania for the man looming on the horizon.

His 1983 novel, Der Untergeher (translated in 1991 as The Loser) has Gould as a main character. His superiority at the piano leads two other fictional characters to give up their own playing in despair. They become obsessed with Gould — one even kills himself when he hears about his death — and their lives are dwarfed by his legacy. Critic Robert Fulford, who knew Gould and who wrote about the book in Saturday Night, summed it neatly: “In Bernhard’s account Gould’s talent is so large that it’s dangerous as well as sublime — perfect material for a cult.”

His larger-than-life status has been helped by the fact that he was a child prodigy, the only son born to Russell Herbert (Bert) Gould, a successful Toronto furrier, and Florence Grieg, who called composer Edvard Grieg a distant relation. Gould’s mother began to give him piano lessons when he was 3. Alberto Guerrero, who taught him at Toronto’s Royal Conservatory of Music for nine years, reportedly said, “If Glenn feels he hasn’t learned anything from me as a teacher, it’s the greatest compliment anyone could give me.”

Raw talent, so potent and unpredictable, fascinates and mesmerizes. People long to know its source, which is probably one way of explaining the number of foreigners who follow Gould’s life passage: By retracing his steps, they hope to solve at least part of the mystery of his creative power.

One woman who knew him believes the mystery is impenetrable even 35 years after his death. Marilyn Kecskes has been the superintendent of 110 St. Clair Avenue West since 1973. She first met Gould on the elevator, when he was wearing gloves and covering his face with a handkerchief for fear of catching her germs. Kecskes said she had never before met anyone like him: a maverick and eccentric who was also a raging hypochondriac.

She knew he was special, too, because his mailbox was the only one that had been tampered with. Someone had once tried to force it open in hopes of getting a bit of his mail.

Gould was by then an international celebrity, much sought after. English critic Nicholas Spicer notes in a 1992 essay that Gould’s fame was set at the age of 22 when he played for the first time outside Canada, at a recital in Washington. Columbia Records offered him a recording deal immediately after his first performance in New York in 1955. His first recording for them, Bach’s fiendishly difficult Goldberg Variations,became the best-selling classical record of 1956. It confirmed his superstar status and remains in print to this day.

Kecskes took the elevator to the top floor of this still stylish Art Deco building. Gould, she said, was messy (“orange juice and milk cartons everywhere”), and intensely private (he fired his cleaning lady of five years “because she liked to gossip about him”). Kecskes added that he covered his bedroom window with a bookcase, that he was a terrible driver who frequently drove his big Lincoln Continental into one of the concrete pillars in the downstairs parking lot, and that he disliked intrusions. “Once he called me on the telephone,” she said with a smile. ” ‘There’s someone knocking on my door. Could you see what they want?’ Imagine!”

When the elevator stopped, Kecskes opened the heavy doors next to what was once Gould’s apartment and mounted the stairs to the roof. She pointed below to what used to be his window. “I used to sit up here, after I had done my cleaning, and I would listen to him play all night long,” confessed Kecskes, blushing at the memory. “He never knew I was up here, or else he would have been angry with me, I suppose, but I had the moon and the stars and his music and there was nothing more beautiful.”

Not everyone is as enamoured. His detractors say that he was a one-composer musician who played Bach passably and other piano music poorly. Even Leonard Bernstein thought so. In a 1962 performance of the Brahms Piano Concerto No. 1 in D-minor with the New York Philharmonic, Gould played the first movement so slowly that Bernstein, who was the conductor, publicly repudiated the interpretation in advance of the concert. As for Gould quitting the concert stage in 1964 to concentrate on a recording career, his critics say he finally lacked the stamina and composure to perform live. Gould was known to hum, grunt and stomp his way through his piano playing.

In his later years, he became increasingly obsessive about controlling his environment, as well as his personal relationships. Indeed, most of those were maintained over the telephone. He was also an insomniac whose irregular sleep habits — he liked to play and record during the night, then sleep, fitfully and briefly, during the day — undoubtedly contributed to the stroke that killed him.

Tim Vardy, a 22-year-old piano student from The Hague, was in Toronto recently on his Glenn Gould pilgrimage. Sitting at Gould’s historic Yamaha, on display in the foyer of Roy Thomson Hall, Vardy silenced the artist’s detractors with a bang of a hand against the keys of the very piano used to record a second version of the Goldberg Variations in 1981. “There are many great pianists in the world; he just happens to be the most interesting,” said Vardy, launching into his own performance of Bach. “For me what’s special about Glenn Gould is when you hear him play, in a way, it has little to do with piano playing but everything to do with pure music. Sometimes you are not aware that he is playing the piano, it is so direct.”

Vardy wanders off to the Glenn Gould Studio next door in the new CBC building on Front Street. There he spies the Chickering, Gould’s childhood piano. He leans across the velvet rope meant to protect the piano from the public and lovingly strokes the keys. “I like him because he is not conservative,” he said. “What he teaches me about the piano is that there is not one way of playing it.”

BACK at Mount Pleasant cemetery, Alessandro Columbo is smiling so hard he is practically laughing. “Look at the gravestone,” he says, “it is so simple, and so right that it is simple, because it is the essence of Glenn Gould.” He takes a few photographs, then aims his lens at a large boulder. On it is a plaque that commemorates a nearby Sitka spruce, whose wood is used to make the sounding boards of some pianos. Japanese businessmen from Sony, Gould’s record label today, planted it on an earlier pilgrimage, with the help of Gould’s father, at the conclusion of the 1992 International Glenn Gould Conference.

“Canada is the right place for what he was, because it is a country with a short history and not 2,000 years of history, and so it is possible to have more freedom,” says Columbo, climbing slowly back into the car to go to the airport. “I am completely in agreement with Tolstoy, who said art is something new. And that was Glenn Gould. A man too new and very different from what was normal. He was a genius.”

Site specifics:

Here are some key locations in the life of Glenn Gould. Except where indicated, all are in or around Toronto.

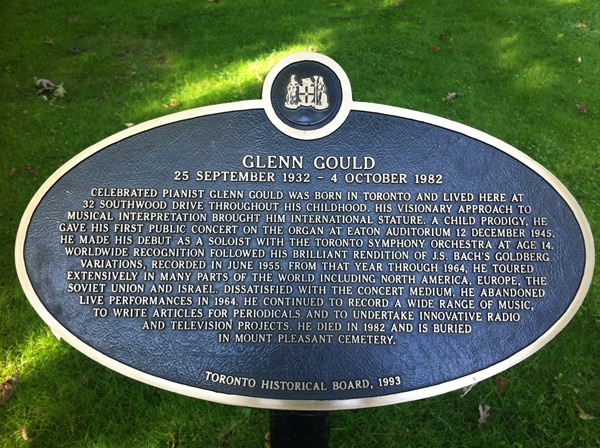

The family home: 32 Southwood Dr., in The Beach district of east Toronto. The family of Robert Fulford lived next door, at 34. Fulford’s father, Russell “Bert,” a furrier and violinist, died in 1996; his mother, Florence, in 1975. A designated historic site.

The music lessons: The Royal Conservatory of Music, 135 College St., (then called the Toronto Conservatory of Music; now the site of Ontario Hydro; RCM moved to McMaster Hall, 180 Bloor St. W., in 1963). Gould began his studies there at age 7, in 1940, and received instruction there through 1946.

The high school: Malvern Collegiate Institute, 55 Malvern. Glenn Gould attended classes here from 1945 through 1951. As a special studies student, he never matriculated. Other Malvern students: Robert Fulford, Don Getty, Teresa Stratas.

The debuts: Eaton Auditorium, College Avenue at Yonge Street, Dec. 12, 1945: first public performance, on organ, not piano (destroyed by fire, 1963); Massey Hall, 178 Victoria St., May 8, 1946: first public orchestral performance, with Toronto Conservatory Symphony, on piano; Massey Hall, Jan. 14, 1947: first performance with the Toronto Symphony.

The apartment: 110 St. Clair Ave. W., Apt. 902 (penthouse). A plaque at the entrance commemorates the 15-20 years Gould stayed there. No admission to general public.

The park: Glenn Gould Park, at the intersection of Avenue Road and St. Clair, northwest corner. Former home of Toronto Music Library.

The pianos: The 1945 Steinway which Gould began playing in 1960 is at the National Library of Canada, Ottawa; the Yamaha concert grand, which Gould used for his final recordings, is at Roy Thomson Hall; the 1895 Chickering, which he played as a youth and kept at his penthouse apartment, is at CBC Toronto, 250 Front St. W.

The churches: Uxbridge United Church, northeast of Toronto, where a five-year-old Gould played his first recital, for the Uxbridge Business Men’s Bible Class; All Saints Kingsway Anglican Church, 2850 Bloor St. W., where Gould, on organ, recorded The Art of the Fugue, Vol. 1 in 1962; St. Paul’s Anglican Church, 227 Bloor St. E., where Gould’s memorial service was attended by more than 3,000 on Oct. 15, 1982.

The gravesite: #1050, section 38, Mount Pleasant Cemetery. Gould suffered a massive stroke on Sept. 27, 1982, just two days after his 50th birthday, and died Oct. 5 at Toronto General Hospital. –Deirdre Kelly

Sources: National Library of Canada; The Globe and Mail; Glenn Gould Foundation; Bruce Cross; Encyclopedia of Music in Canada.

(Originally published in 1997, this article has been edited and updated for this personal blog. I am the author.)