Carved In Whale Bone: The Art of Manasie Akpaliapik

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

In a lush part of Southern Ontario, Baptist churches grow as thick as corn stalks and Manasie Akpaliapik is far from his birth place at a hunting camp north of Baffin Island.

Yet the Inuit sculptor is reminded of his polar roots each time he takes a hammer and chisel to the huge chunk of whale bone that his hunter-father recently sent him.

He would like to have the sculpture ready for an exhibition of his work opening soon at the Indigena Gallery in Stratford, Ont. But the internationally acclaimed artist (he has work in the Canadian Museum of Civilization, the Art Gallery of Ontario, the Winnipeg Art Gallery, the National Gallery of Canada and the Art Gallery of Nova Scotia) is beginning to see the whale bone as the elusive Moby Dick.

“I have been having a hard time with this piece,” he says softly in slow, clipped English. “Maybe the size is scaring me. I don’t want to make a mistake.”

He puts the chisel down and picks up a pack of cigarettes. Small and muscular with high, flat cheekbones and hair as dark as a crow, Akpaliapik remains silent a long time as he contemplates the gnarled and porous hunk of skull before him.

“Sometimes you can look at a piece and it says nothing, and the next day suddenly it’s all there.”

Inspiration, he adds, swatting a mosquito, is being able to see something before it actually exists.

As it turns out, the whale bone will not be ready for the Stratford show. But Indigena Gallery owner Erla Arbuckle has about 20 other sculptures by Akpaliapik to showcase.

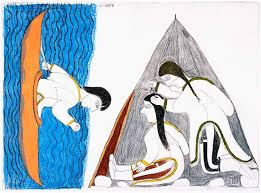

“I don’t want to call it a spirit show,” she says, “but I have looked for pieces that show transformation, and that bring elements of the spirit world in contrast with elements of the natural world.”

It’s something of a long story as to why an Inuit lives on an Indian reserve, but the short of it is that, because Akpaliapik’s wife is half Ojibwa and half Irish, he is permitted to set up house on land usually reserved for Six Nations people. Living there has convinced Akpaliapik that Inuit and Indians are similar:

“A lot of our beliefs and how we see nature and the land and the weather is pretty much the same.”

He looks forward to the Indigena exhibition because, in its own small way, it will show the two peoples as united.

Akpaliapik’s style, meanwhile, is not easy to define. He is interested in nature, but his work is never the naive realism of, say, airport Inuit art. Rather, his work bristles with ideas, most having to do with relationships between humans and nature, humans and the spiritual world.

Akpaliapik leaves the whale bone for a moment and walks across his back yard to a recently finished carving that sits on a cement brick in the full light of the afternoon sun.

Made out of antler, alabaster and animal bone, the three-dimensional sculpture shows from the front an Inuit face and from the back a full-bodied seal. Tenderly holding it in his hands, Akpaliapik, who was born in 1955, says his inspiration for this piece came from the seal hunters he knew in his youth.

“In my area, as I was growing up the main food source was the seal. We used it for rope, for clothing. For us it was a life source. And for me, if that seal were not there, that person would not be there.”

In addition to whale bone, Akpaliapik’s materials include caribou antler, narwhal tusk and polar bear bone.

Although he has often come into conflict with U.S. export restrictions governing whale bone and other ivories, Akpaliapik stresses that the natural materials he uses come from animals that died in the wild.

He also sculpts in limestone, alabaster and Italian marble. But he prefers animal materials because they have shapes that inspire ideas and because they strengthen ties linking his art to his roots. “It keeps me in touch with Mother Nature too,” he says.

Carving is part of his family background — his grandparents, Elisapee Kanangnaq and Peter Ahlooloo, are well-known carvers from Arctic Bay, and his great-aunt, Paniluk Qamanirq, is celebrated for her abstract sculpture.

But Akpaliapik, who lived a nomadic life before being forced to attend school at the age of 12 — “I moved three times a year according to the seasons” — did not start sculpting full-time until a tragedy forced his hand.

He was 24 and working, as many Inuit do, on an oil rig hundreds of kilometres away from his community. One night, while he was at work, his first wife, Noodloo, and their two small children, a boy and a girl, died in a house fire. “It just happened when they were sleeping,” he says, his head bent low over his carving.

After the accident, Akpaliapik moved to Montreal where he lived with a group of sculptors. That’s when he transformed himself into an artist. “It was a way of healing myself.”

He lived in Montreal for five years, then moved to Toronto with his second wife, Geralyn Wraith, a makeup artist. They bought a house in the east end and had a son, now eight years old, named Kiviuq. Their house at Six Nations is used mainly by Akpaliapik as a studio retreat.

Akpaliapik named his son after an Odysseus-like figure in Inuit folklore who travels the universe on a series of life-affirming journeys.

His story, says Akpaliapik, “gives up a different window on different situations and different problems. A lot of people, when you get stuck in life, think of this legend to get some ideas as to how to get free. Also, I’m so far down here and I guess I just felt that it was an appropriate name for my son because it tells him who he is and where he comes from.”

He has carved the Kiviuq figure in the past and says he has often looked to the legend to help him in his own times of trouble.

“All these years I have been struggling with alcoholism, like a lot of my people have been. When you go through drastic changes you kind of turn to alcohol or something else to get away from reality,” he says.

One of his pieces in the National Gallery is a sculpted portrait of a man gripping his head, eyes rolled back in their sockets, the mouth an open grimace of pain. Out of the top of the head rises a meticulously carved wine bottle. Akpaliapik says it’s a self-portrait: “And maybe I was hoping that if it comes out in the art it will make people realize that it [alcoholism] is their problem too.

“A lot of time my art helps me cope with things,” Akpaliapik says. “Sometimes there are things that I can’t talk about, but it will come out in my art.”

(Originally published in The Globe and Mail on July 13, 1996)