GRACE NOTES – HOW GRACE MIRABELLA WENT IN AND OUT OF VOGUE

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

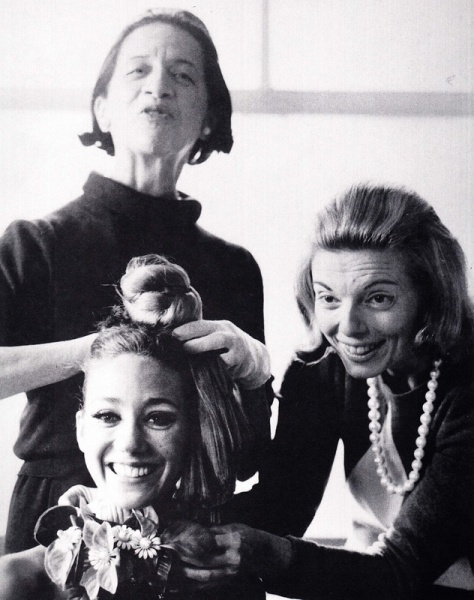

WHEN Grace Mirabella became queen of Vogue magazine in 1971, succeeding Diana Vreeland, the kooky, flamboyant high priestess of fashion, the then- fortysomething daughter of Italian immigrants signaled the changing of the guard by repainting the crimson walls of the editor-in-chief’s office a sobering beige.

Mirabella’s detractors had a field day. John Fairchild of Women’s Wear Daily sneeringly called the Newark, N.J., native “practical,” while Hebe Dorsey of the International Herald Tribune solemnly pronounced that she marked the “end of the era (of) haute couture.” Andy Warhol, once “a soul mate,” lisped that she had been given the job because “Vogue wanted to go middle-class.” Newsweek dubbed her “a nine-to-five” girl.

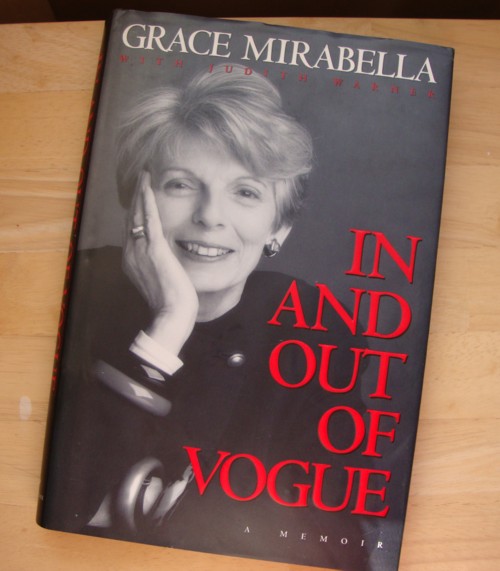

These were fighting words. Mirabella eventually jabbed back with her 1995 memoirs, In and Out of Vogue, meeting with members of the press on a book tour to relish her moment of revenge. I was one, meeting her in a Toronto hotel room where she promptly put to rest those critics who accused her of not being “fashion-y enough.”

“That suits me fine,” she said at the time, “if being the opposite means accepting with open arms every backless and frontless and topless and see-through thing that clomps its way down the runway in combat boots.”

Much of In and Out of Vogue is an effervescent tribute to a bygone era of style and glamour. Written with the wry observation and loping stride of an F. Scott Fitzgerald novel, her book also makes room for that stock-in-trade of the fashion biz: bitchy comment. Photographer Richard (Dick) Avedon is depicted as a screaming ego who “achieved his best effects with girls who were utterly strung out on dope.” Warhol, Candy Darling and hangers-on of Warhol’s Factory scene “smelled like unwashed underwear”; the late designer Halston is described as a glutton for nose candy and Yves Saint Laurent as a drooling drunk.

But to appreciate what Mirabella inherited at Vogue at the dawning of the disco age, one must recall the Vreelandese of the decade before: Everything was “very now,” “very happening,” “very up, up, up.”

Such high-energy declarations may well have been in keeping with the drug-induced frenzies of the sixties, but they were totally out of touch with reality in the seventies. Women were entering the work force in record numbers, they were burning their bras, their girdles, their marriage licences; they were becoming antifashion; worse, they had stopped buying Vogue.

“The age of the Beautiful People was over, I felt, gone the way of Aquarius,” Mirabella told me. “I wanted to give Vogue back to real women. And even though I’d repeatedly been told that my idea of reality as seen in Vogue bore no resemblance to the real thing, I still wanted to create a new image of reality, a heightened reality, as I always called it, that would show women working, playing, acting, dancing . . .”

Vreeland’s vision alienated vast numbers of readers who couldn’t – or wouldn’t – wear her “duh-vine” purple see-through blouses to their new jobs. Newsstand sales of the magazine plummeted; in the first three months of 1971, sales of advertising pages at Vogue had fallen a full 40 per cent. Vreeland’s go-go boots were walking the magazine straight into oblivion.

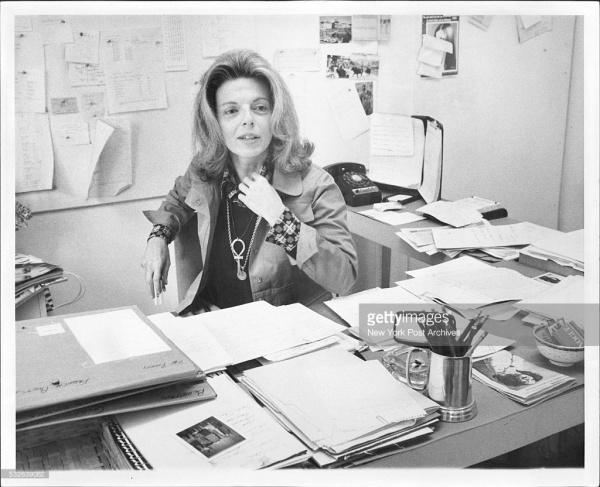

Senior management at Vogue saw that change was needed. So out went Vreeland and in marched Mirabella, a long-time employee who had risen from gopher to stylist to assistant to editor. And even though Vreeland’s supporters looked down at Mirabella as oh-so-boring, “real” women came to see her as a godsend. As did the company executives who basked in the glory of Mirabella’s success in raising Vogue circulation from 400,000 in 1971 to 1,245,000 in 1987, when she left the magazine after 17 years.

The upstart editor-in-chief wanted to show women “doing things that mattered in the world and wearing clothes that allowed them to enjoy them. . . . I wanted to make Vogue democratic – not middle-class in the sense of being pedestrian or narrow-mindedly moralistic or down-market, but in being accessible to women like me.”

The “me” in question stared down with muzzled disgust at her lunch. The tuna sandwich was, well, more than she expected. She lifted up the upper piece of bread and looked inside and saw olives, a boiled egg and lettuce. The tuna is there but covered up by all this stuff. “Anything wrong, madame?” a nervous waiter asked from the sidelines. “Not really. It’s just that I feel overwhelmed.”

The polite but firm refusal of this lunch-hour repast was perfectly in keeping with Mirabella, a woman for whom the credo ‘Less is More’ seems to have been invented.

“To me, fashion has always been a vehicle – a fascinating, sometimes magnificent vehicle – for helping women enjoy and delight in their lives. Fashion to me isn’t, and never has been, an end in and of itself. You’ll never find me getting excited about shoulder pads or caring deeply, one way or the other, if hemlines went up or down. . . ,” she said. “What I’ve always cared about, passionately, is style. Style is a way a woman carries herself and approaches the world. It’s about how she wears her clothes and it’s more: an attitude about living.”

That is her philosophy. She lives and breathes it. Still.

Dressed on that day in a Bill Blass tailored suit, Mirabella is the personification of “the new ease” and “the new informality” that characterized her reign at Vogue – a long way from the Vogue of 1892 when the New York magazine was founded as the “dignified, authentic journal of society.”

Blass, the U.S. designer Mirabella championed in the seventies along with Halston, Ralph Lauren and Geoffrey Beene, all fulfilled her ideal of “interesting fabrication and marvellous cut and proportion.”

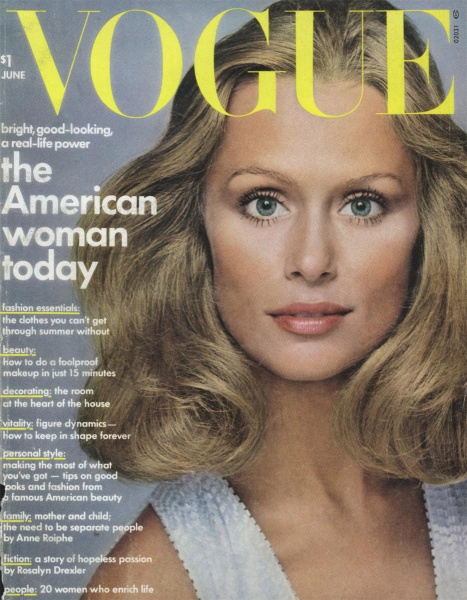

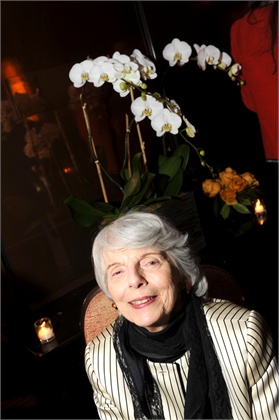

Vreeland’s “fashion is theatre” became Mirabella’s “fashion is freedom.” The changing esthetic was captured by a bevy of new bodies and faces – Lisa Taylor, Karen Graham, Patti Hansen and Lauren Hutton – who effortlessly embodied Mirabella’s “beautiful-tomboy type.” It’s easy to see why she liked those supermodel prototypes: Mirabella, with her wheat- blond hair cut in a shaggy style and barely-there makeup palette (pale eye shadow, a bit of liner, plum lips and a splash of Bulgari eau de parfum), exemplifies the “relaxed and spontaneous” glamour that was her hallmark.

Nevertheless, fashion is notoriously fickle. In 1987, just as unceremoniously as her predecessor, Mirabella, the woman who had made Vogue an almost worldwide arbiter of taste and standards, was unceremoniously fired by the suits who had put her in power.

Then 57, Mirabella found out about her dismissal on the evening news when her friend, society columnist Liz Smith, announced that she had been usurped by 39-year-old Anna Wintour, formerly editor of British Vogue and the revamped House and Garden. She was, the fashion press wagged, a much younger woman. Mirabella, a class act through and through, uttered a terse comment to the New York Times. “For a magazine devoted to style, this was not a very stylish way of telling me.” Those who once thought she was boring now said she was just too fabulous to lose.

“I should have been depressed. But instead I felt oddly elated,” she says of her abrupt departure from the magazine where she had worked for 38 years. “It had been at least two years since I had first wanted to leave Vogue, but I never had the nerve to go.”

Management had been hassling her to make the magazine more like Elle, the new kid on the block. They wanted to capture Elle’s MTV sensibility: trendy, cartoon-like, light on text, heavy on jokey fashion modeled by young and adorable girls. But Mirabella refused, saying, “I didn’t know how to edit a ‘lite ‘n lively’ Vogue.”

She landed on her feet. Rupert Murdoch asked her to start up her own namesake publication. Mirabella, a thinking woman’s “style” magazine, hit the stands in June, 1989, and hit hard – selling out all 525,000 copies.

Advertising sales at first soared but then wavered; reader response was at first good but then critical, after the magazine, under the editorship of Gay Bryant, a Murdoch magazine maven, introduced waif-like models, drab clothes and depressing articles – much to Grace Mirabella’s horror. (Mirabella admits having lost control by that point, when she allowed Murdoch to reassign her to “an ancillary, hand’s-off position.”)

The magazine was also a money-guzzler. Murdoch eventually closed, then sold it in 1993. The publication that industry insiders like to call “the magazine born with a silver spoon in its mouth” was then briefly resurrected by Hachette, the organization that owns Elle. Amy Gross was made editor and Mirabella was renamed “consultant,” sometimes a kiss of death.

“When people call you ‘consultant,’ it usually means there’s no going back,” she said.