Ode to the Turtleneck

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

It’s one of the first places to show your age, and one of the hardest to lift, peel, de-sag. We’re talking about the neck. It is the pillar on which rests the noble head, girded by gold or precious stones. It is the home of the throat and a shelter for daubed perfume. It is an erogenous zone where noses nuzzle, lips linger and hickies bloom like obscene hothouse flowers. The neck is powerful. And clothing designed to showcase it is equally potent, perhaps none so much so as the turtleneck.

The high-collared sweater is a staple of most people’s wardrobes, men and women alike. Its perennial popularity stems from its close-fitting, uncluttered lines, as well as its promise of warmth — an especially welcome feature for those of us about to enter a savage Canadian winter. But for the aging baby boomer, the turtleneck has emerged as one of life’s essentials, as important as ginseng and weekly colonics. And all because the turtleneck conceals.

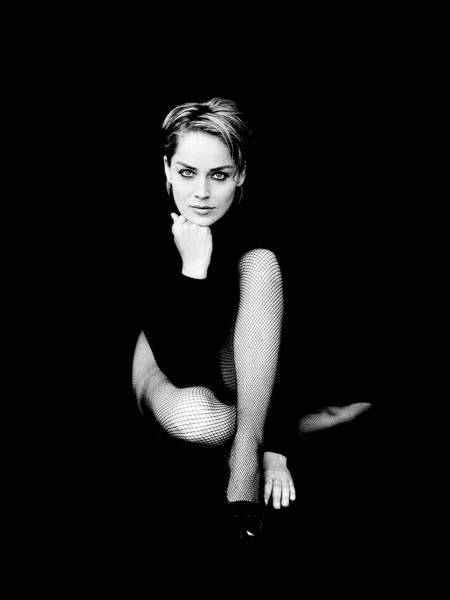

No wonder a senior style-setter like Kate Hepburn was never seen without it. The turtleneck flatters and rejuvenates — no knives, no pills, just a simple roll of cloth. It also sexes you up. Witness Sharon Stone who wore a sleeveless Gap pullover to the Oscars in 1996. Out of the funnel came a goddess.

But it wasn’t always a shortcut to vanity. The turtleneck’s origins are on the contrary, prosaic. Historians identify 1860 as the year of the turtleneck’s quiet birth on the brackish fields of England. It was exclusively a man’s garment. Members of the shooting class wore turtlenecks to hunt. Sitting close to the body, with a tubular collar that kept the chill from the bone, the turtleneck was a discreet undergarment, stylish only by association with the gentry, who wore it strictly under wraps.

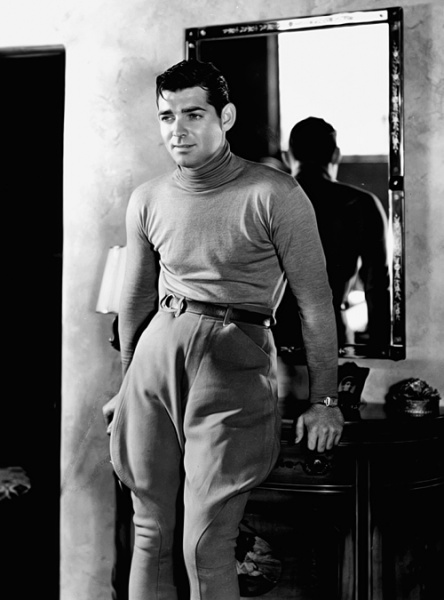

Noel Coward, the jaunty, ironic playwright and composer, himself of the manor-born, was the first to lend the turtleneck its cachet as a fashion item. Coward subversively pulled the turtle from out of its shell in the 1920s. He wore it defiantly on its own, under a jacket. No top shirt to lend it respectability. Hollywood actors Clark Gable and Robert Coleman soon adopted this roguish look, and turned the turtleneck into the epitome of glam.

Never one to let boys have all the fun, designer Coco Chanel was determined to give her women clients the sense of freedom in clothes enjoyed by men. She threw out the bustle, streamlined the silhouette and gradually, over six decades in fashion, appropriated several items from the male wardrobe for her haute couture. Among them was the turtleneck, the new badge of androgynous chic. Chanel paired it with natty suits and decorated it with her trademark ropes of pearls. She made the turtleneck proper. But screen siren Marlene Dietrich, who adopted the turtleneck as part of her femme-fatale uniform in the 1930s, made it dangerous by pairing it with a black beret and dangling cigarette.

With women of high style now wearing it, the turtleneck became a fashion icon. You could almost measure morality by it. What had begun as something practical had morphed into an emblem of iconoclasm. When you wore it, you exuded attitude: You were a loner, a freethinker, one who walked on the wild side.

No wonder the existentialists of post-war Paris adopted the turtleneck as their uniform. And the colour, of course, was black. Aspiring Jean-Paul Sartres everywhere took note.

The beats in New York took the look and made it ubiquitous in the smokey cafes and jazz bars of bohemian Greenwich Village. William S. Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch and father figure to several chemically dependant generations since his authorial debut in the 1950s, wore the black turtleneck through to the end of his days in the 1990s. It was a symbol of rebellion.

Beatniks, or weekend hippies who wanted to flirt with the danger-beat poets like Burroughs represented, appropriated the turtleneck. And like all outre trends absorbed by the masses, they made it safe. Worse, they made it cute.

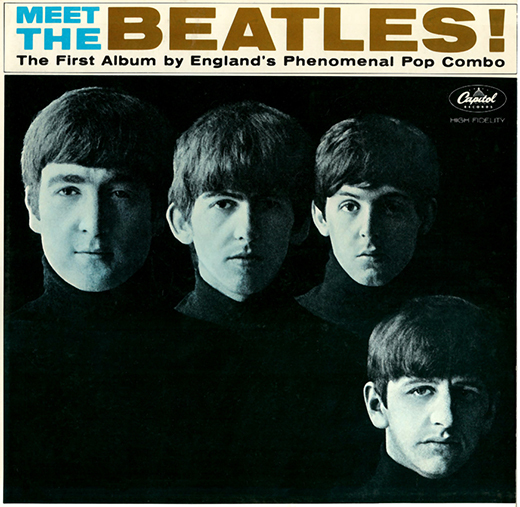

The new darling status was personified by an ingenue named Audrey Hepburn in the 1957 film Funny Face. She paired the black turtleneck with black capris and ballet slippers. By softening the existentialist edge, she made the black turtleneck look effortlessly elegant. Coco Chanel must have been proud. Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar paired it with cocktail skirts and pencil-thin trousers. Manufacturers, responding to the demand, made them fast and cheap, while high-minded designers lent them an air of luxury with costly fabrics like cashmere and silk. Rich or poor, no closet was without one. Marilyn Monroe wore hers with jeans and heels. The Beatles, meanwhile, paired theirs with long hair for their North American debut record, Meet The Beatles. The black turtleneck was sexy, cool, glamourous, proletarian — a sweater for all seasons, and reasons.

Its standing as a democratic item of clothing continues. On the catwalks of Europe, in the shopping malls of the globalized world, the black turtleneck rules. It is poised for winter but just as ready for spring, where designers like Miuccia Prada are forecasting its return paired with smart pretty skirts and strappy sandals. This is doubtless good news for boomers. If you’ve got to girdle your neck anyway, how comforting to know that it is in service of high style.