And The Stars Look Very Different Today — Farewell David Bowie

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

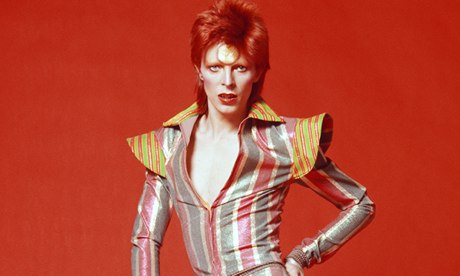

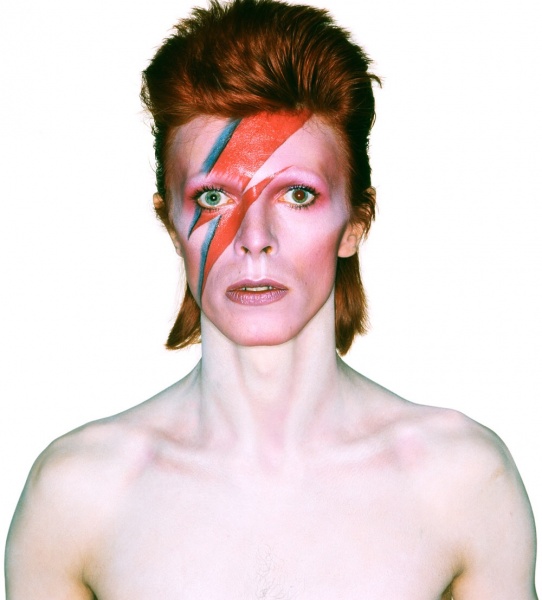

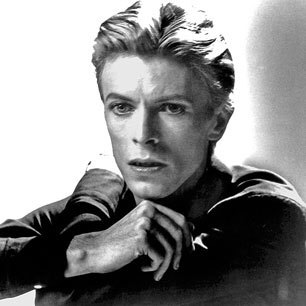

David Bowie. Just his name conjures so much — music, movement make-up and more, all wrapped up in memories. As an aesthete-in-training who lived in Toronto in the 1970s, his songs about wayward identities with fabulous closets were like doors that led me into a world where being different was not just okay, it was the only true route to self-expression. Living your life like a work of art. I slept with his albums under my pillow, absorbing his rebel, rebel spirit as if by osmosis. I felt a sort of kinship with him. David Bowie, with his peacock feathers and mane of hair dyed orangutan orange, was my spirit animal. I was sure it was me he was singing about in “Life on Mars.” Truly, it was uncanny how accurately he narrated the sad chapters of my existence, as I saw it anyway, at that time:

It’s a god-awful small affair

To the girl with the mousy hair

But her mummy is yelling “No”

And her daddy has told her to go

But her friend is nowhere to be seen

Now she walks

through her sunken dream

To the seat with the clearest view

That strong sense of connection made David Bowie not exactly my idol, but more my confidante if not alter ego. I would be weepy at times listening to him sing to me (of course as a tortured 14 year old that is how I imagined it). But, and blame it on the raging hormones, I could just as easily be energized by his rocking beat.. I made up dance routines to “Suffragette City,” which I performed with my best friend and fellow Bowie conspirator Susan Willemsen, at parties held in other people’s parents’ basements.

The chorus, ‘Wham! Bam! Thank-you m’am,’ had us going down first on one knee, then the other before standing and kicking before turning quickly to face each other at either ends of the room. The point was not to engage with others in our midst. It was to mark ourselves as different from the ho-hum crowd, and precisely because we had David Bowie in our camp.

David Bowie was a beacon of individualism in a beige world. He was what helped me survive the stifling boredom of growing up in staid, artless, conformist Toronto, a city I vowed to leave one day but then never did. Bowie and his tribe of glam rock troubadors made bright my existence when it felt most drab and stultifying. Bowie especially focused my attention on the power of artistic expression to forge an identity that would be its own sense of comfort.

As a young adult, I got my job at Canada’s national newspaper, writing on dance and also for a few years the music that had once sustained me. As part of my job, I had two close encounters with David Bowie. The first was a Toronto press conference (at which Bowie’s old school friend and co-musician, Peter Frampton, was also present) and the second an interview conducted as part of a feature I wrote on Bowie and dance during a break in the 1987 Glass Spider tour.

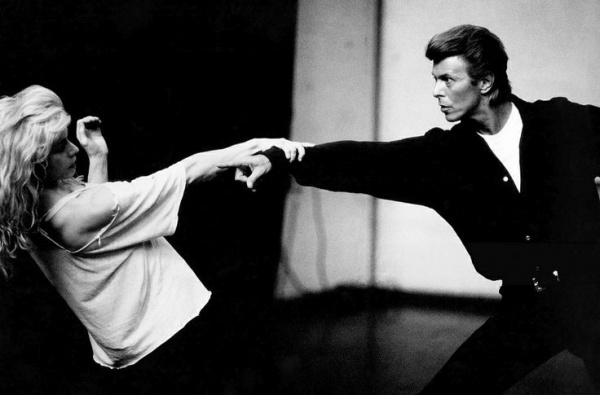

As luck would have it (or had it all been pre-conditioned from listening and watching him all those years before?) David Bowie shared my love of dance. In the 1980s, he forged a decade-long professional relationship with Montreal choreographer Edouard Lock and Lock’s star dancer, Louise Lecavalier. She danced with Bowie in the 1990 Sound +Vision your and also appeared in the video for “Fame.” I was one of the first to report on their collaboration for The Globe and Mail. I also reviewed the concert tour in which Levacalier performed with the band before millions of screaming fans. Just months ago I asked Louise what that was like and she described it as a “big kick” that gave her “wings on stage.” She also called Bowie one of the sexiest dancers alive.

For this who might not be aware, David Bowie had trained in dance early in his career. His mentor was the great Lindsay Kemp whose flamboyantly theatrical style also influenced Toronto choreographer Robert Desroisiers. The Thin White Duke danced in his own shows and videos. He sought out dancers as partners, both on and off stage. Dance and dancers always held a strong connection for him. It wasn’t a passing fad. Even in the video for his song, “Lazarus,” released just days before his death, Bowie can be seen reverting to the pantomime taught him by Kemp. He also dances, abstractly, before a closet into which he ultimately hides his skeleton.

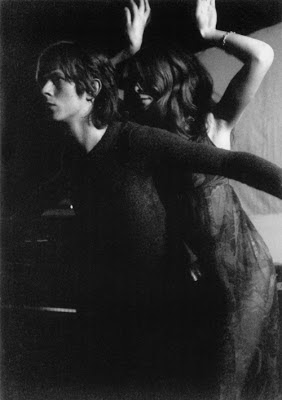

His first real love was the classically trained dancer Hermione Dennis (later Farthingale) whom he met in 1968 on the set of the British film, The Pistol Shot. They danced a minuet together as part of a group of dancers led by Kemp.

Soon after they became a couple, living together in London, they formed a group, Feathers, which was to set in motion Bowie’s discovery and signing by Mercury Records. Hermione, who later danced with the Welsh Opera Ballet and in such British films as Ken Russell’s The Boyfriend, eventually left David Bowie for another dancer in 1970, leaving him heart-broken. He tried to woo her back through messages in songs like the obviously titled, “Letter to Hermione,” among others. The beautiful dancer is the real girl with the mousy hair alluded to in “Life on Mars.” But she would not return to him. In interviews, Bowie said he was “devastated” by the breakup and the loss of Herminone led him to embark on his “Space Oddity” persona and subsequent otherworldly artistic voyage.

His next lover, and eventual wife, met him at the time of the breakup. Angela Barnett was not a dancer but a savvy and quite brilliant marketer who knew how to sell her future husband to the masses. Together, they had a son, Zowie Bowie, now a filmmaker who goes by the name of Duncan Jones. But the marriage didn’t last. They divorced in 1980 when Bowie’s unquenchable hunger for drugs and ambi-sexual extra marital affairs grew too much for his wife to handle, or so she says. He once said living with her was hell. Duncan has not spoken to his mother in years.

In his 40s, Bowie became romantically linked with another dancer. I interviewed her in Toronto. Melissa Hurley was then one of several dancers performing in the 1987 Glass Spider tour. She was more than 20 years his junior at the time and frequently photographed with Bowie until his marriage to the Somali-born supermodel, Iman, in 1992.

I spoke with Melissa perched on a lounge chair next to the Four Seasons’ pool. David Bowie had let me know in advance that he would sit the interview out. In a Fax (this was before email), he said he wanted to watch over the discussion from a distance and not be directly involved. He said that he wanted his dancers to get the lion’s share of attention. He would remain in the shadows.

As if.

Even absent he was very present, as I imagine he will continue to be despite having passed on. Some of that ineluctable presence is captured below, in just two of several article I write on Bowie, and which I reprint here in tribute to an artist who meant so much to many — myself included.

Bowie’s new image takes to ‘the streets’

18 March 1987

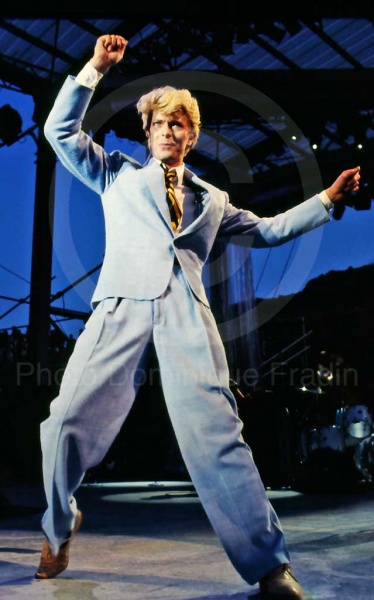

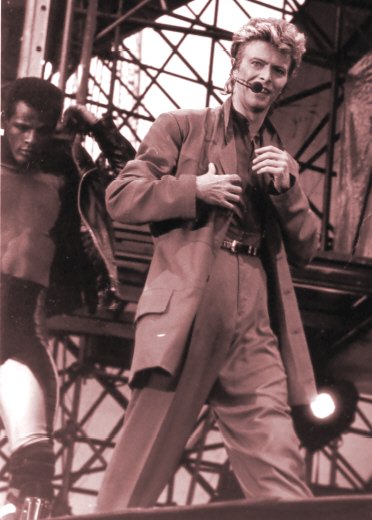

ON THE EVE of the world-wide release of his newest single, David Bowie surprised a media audience at Toronto’s Diamond Club yesterday afternoon by performing two songs from his forthcoming album, Never Let Me Down. The 40-year-old rock star also held an informal press conference and announced plans for a world tour that will kick off in Rotterdam in May and travel across Canada this summer.

Sporting a black leather jacket, studded jeans, open shirt and shiny gold crucifix at the neck, Bowie looked like the traditional, urbanized rock and roller – a grittier image than the aristocratic persona he presented on his Serious Moonlight Tour in 1983.

The new look apparently is in keeping with the tone and subject matter of his latest album, which Bowie said “deals with the streets . . . and attitudes about an uncaring society.”

After performing his new single, Day In, Day Out (released today) – and before performing his second song, 87 and Cry (also from the new album) – Bowie opened the floor to questions. He introduced his five-piece touring band, which includes bassist Carmine Rojas, long-time collaborator Carlos Alomar and English guitar hero Peter Frampton, then pulled up a stool and relaxed.

Laughing and affable, Bowie signed autographs as he fielded queries from the assembled TV, radio and print journalists. He promised this year’s tour will be “very theatrical,” in contrast to his relatively minimalist 1983 tour. For the first time since his Diamond Dogs tour in 1974, Bowie will use a choreographer, Toni Basil. He said the tour will include “sets, costumes, make-up and . . .” (as a humorous postscript, pointing to his teeth) “floss.”

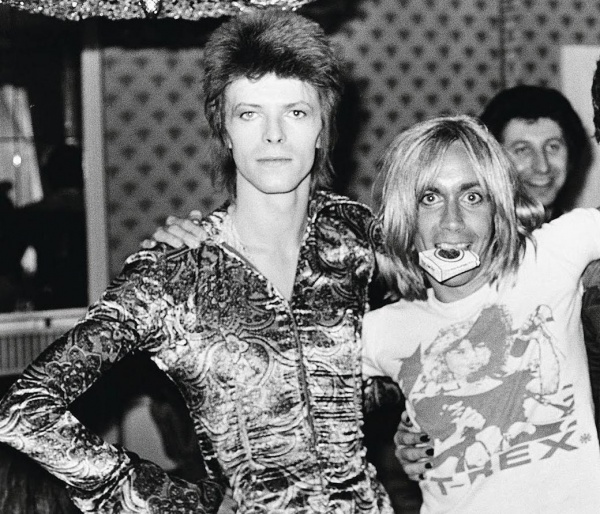

Bowie said the music on the new album, which was produced in Switzerland and will be released on April 20, was influenced by the production work he did on Iggy Pop’s latest record, Blah, Blah, Blah. Bowie decided to imitate the stripped-down rock and roll sound, composing all the songs ahead of time “instead of my usual method of writing in the studio. It’s a high-energy LP with 11 tracks, all written by me, except for one Iggy Pop song. Other people cover Chuck Berry and The Stones. I cover Iggy Pop.”

Bowie added that the style of the new album was also inspired by some of his biggest musical influences – Little Richard, Smokey Robinson, Bob Dylan and Prince.

While Bowie evaded questions about why he chose Toronto for his press conference (“I had the day off . . .”), he was more candid about enquiries about movies (“David Lynch is my favorite director”), music (favorite current groups are Screaming Blue Messiahs and The The), a proposed movie with Mick Jagger (“It’s in the air”) and the first video for the new album, directed by Absolute Beginners’ director Julian Temple.

“It’s a street video, about the homeless situation in Los Angeles. We hired a lot of homeless people from the streets, some of whom had formed themselves as a theatre group. It’s quite strong as far as video goes. I don’t usually do performance videos. I try to use video in certain ways . . . to make fundamental social and artistic statements.”

Bowie’s new band had a rollicking sound that is more guitar-oriented than anything Bowie has done since the early seventies. The presence of Peter Frampton emphasized Bowie’s return to the brighter, street-oriented sound of the early seventies.

Bowie and Frampton were schoolmates in London (Frampton’s father, Opie Frampton, was Bowie’s art teacher) and are long-time friends, though this is the first time they have worked together professionally. Frampton was on tour in Toronto as the opening act for Stevie Nix last year when Bowie telephoned him.

“David called me and asked me if I’d play on the album,” said Frampton, “and I was thrilled about it. Then when were working on the album, he asked me to go on the road.” Bowie said he feels no sense of competition with his 1983 tour, which set audience records in Edmonton and Vancouver.

“I never feel a sense of competition with myself. I finish a tour, and then I say, ‘Why on earth do I do this?’ A year later I say ‘That was sort of fun, wasn’t it?’ Then after another year, I think about it a little more. The next year I’m busy writing songs for the next album and getting ready to go out again.”

Dancing for Bowie tour demands versatility, stamina

29 August 1987

YOU DON’T have to be a fan of David Bowie to dance to his music. Melissa Hurley , 21, and Skeeter Rabbit , 26, are two Los Angeles-based hoofers who found their way into Bowie’s cabaret-styled Glass Spider tour almost by accident.

Hurley, whose mother was a ballerina, is a classically-trained dancer from Burlington, Vt. Her black curls and cherubic face were featured on the hit television series, Fame, for the three years prior to the show’s recent demise.

Until the Glass Spider tour, the only concert she’d ever been to was one by Air Supply. She hardly knew who David Bowie was. “It probably has a lot to do with my age and my dance training. You can be pretty sheltered, you know.”

Hurley’s agent told her about the auditions for the Bowie tour. There had already been a cattle-call in New York for about 250 dancers. Bowie, and his choreographer Toni Basil, saw no one they liked. In Los Angeles, where another 250 auditioned, they came up empty handed again.

Hurley, who was auditioning for another show that day, had left her photograph and resume with Basil who then showed it to Bowie. Basil called her. She didn’t care if Hurley had another show to do, they wanted her to audition. She did a gruelling seven-hour haul that required her to dance in evening gowns a la Pina Bausch, bump and grind her way through selected choreography by Montreal’s Edouard Lock, perform the solo from the nineteenth-century “killer” ballet Raymonda, and do a series of movements based on improvisation.

“The day was long and tedious,” said Hurley. Her performance was recorded on video. Bowie saw it and liked her style. She was then offered a nine-month contract. Hurley decided to forego the other job and go with the tour. She never met Bowie until the show went into rehearsal.

Rabbit’s strapping athletic frame makes him an easy contender for his favorite football team, the Dallas Cowboys. Born in Texas, Davis grew up in Los Angeles where he was a street-gang leader as a boy. Unlike Hurley, Rabbit has next to no formal training. By his own admission, he’s got plenty of personality and charisma. That, more than the ability to gyrate hips on command, is what landed him a position with the tour.

Rabbit, a part-time model and actor, had just come back from a modelling assignment in Japan when Basil phoned him with a proposition. She said she had someone she wanted him to meet. Only when they were in the lobby of Bowie’s hotel did Rabbit learn who he was going to meet.

“I was shocked. I had danced to his music when he switched to more of a black, funk sound, like with Golden Years, Fame, Young Americans – stuff like that,” he drawled. “I talked to him that day for about 45 minutes. He asked me to show him what I could do. He said he wasn’t interested in last year’s style. He wanted something totally new, something of the future, a new direction. I danced; he liked it.”

Bowie wanted to see Rabbit on video and Rabbit, knowing he wanted the job, threw in some rap with his street dance moves. “I think David was more impressed with my character. I gave myself an advantage by letting my natural character come out – the ham, the show-off.”

Hurley and Rabbit, together with three other L.A. dancers – Constance Marie, Viktor Manoel and Spazz Attack – are contracted to do the tour for nine months. They are each paid a weekly salary of approximently $2000 U.S. plus a a daily spending allowance.

The tour, in Montreal tomorrow night, will wend its way back through the United States in the beginning of September with an added engagement at Madison Sqare Gardens Sept. 1 and 2. The tour ends Sept. 19 in Tampa, Fla. It’s exhausting work. The dancers perform an average of three two-hour shows a week. But Hurley and Rabbit say they are used to it. “Only when you crawl into bed at night do you remember you’re tired,” said Rabbit.

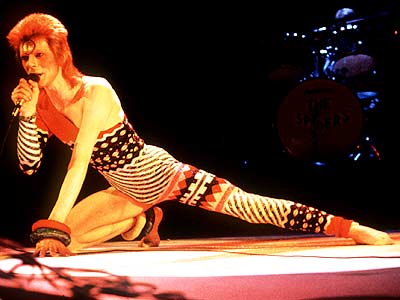

The Glass Spider tour is a 350-ton production that brings a fresh twist to the traditional rock music venue. Bowie conceived the idea for the tour about a year ago. He wanted something challenging, said his touring assistant Sara Gabrels. He was looking to create something more along the lines of a rock/theatre piece, she added.

The show, an extension of Bowie’s long association with the theatre (he is a disciple of dance and mime artist Lindsay Kemp, also the former teacher of Toronto’s Robert Desrosiers), could be on Broadway.

Stylized choreography walks hand-in-hand with dramatic vocalization, improvisation, elaborate sets, colorful props and vivid, theatrical lighting. The entire spectacle is captured on screen by five video cameras that shoot the performers throughout the show.

Film clips appear sporadically on a back screen. Images of bombs, protest marches, ailing politicians and police states underscore the show’s message of global disintegration. “It’s purposeful in its fragmentation,” explained Gabrels. “David crafted it after German theatre of the late twenties and early thirties. Its style is meant to reflect the way the world is – you always get things in fragments.”

The choreography in Glass Spider is disjointed. Rabbit and Hurley, after some discussion, finally agree the show is about 70 per cent choreography, 30 per cent improvisation. Only a few numbers are fully choreographed – Fashion, Scary Monsters and Aliens.

Rabbit said Basil created the choreography out of the personalities of the dancers involved. Each plays a character on stage; Hurley’s is known as True Love, Rabbit’s as The Hero. Basil designed who should do what to what song. “But what we are on stage,” said Rabbit, “is what we’re like off-stage. They (Basil and Bowie) just took it to an extreme.”

Rabbit and Hurley don’t think their roles are crucial to the show’s meaning, “As far as the dance is concerned, it’s just dance where all forms of movement are applicable and where all kinds of dancers can relate to each other and interconnect,” said Rabbit. Still, their words suggest that behind it all is a mesage of universality.

“David loves the avant-garde. He has always been ahead of the game, always before his time,” said Hurley, who, since landing the job, has bought every Bowie record she could lay her hands on and become a big fan.

“He’s international and intricate,” added Rabbit. “He goes into people’s garages and finds talent everywhere. We were chosen, not because we are the greatest dancers in the world, though I hate to admit it, but because there was something he saw hidden in us, an innate quality that needed to be personified.” Rabbit takes a deep breath, lowers his eyes and blushes. “I’ve never idolized anyone before, but he’s so broad – he finds something in everything and gives it life.”