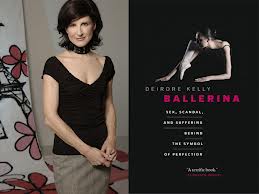

The Santa Fe New Mexican Reviews Ballerina: Sex, Scandal and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection Book

Posted by Deirdre | Filed under Blog

Michael Wade Simpson

Ballerina: Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection by Deirdre Kelly, Greystone Books, 272 pages

Forget any assumptions you may have about the glamorous lives of prima ballerinas. Deirdre Kelly, a Toronto-based dance critic and journalist, has written Ballerina: Sex, Scandal, and Suffering Behind the Symbol of Perfection, which makes Black Swan look like a Disney classic for kids. The cliché of suffering dancers in bloody toe shoes is the least of it in the story Kelly presents. Her version of ballet history is filled with prostitutes, anorexics, and tragic figures like Emma Livry, one of the great Romantic ballerinas of the Paris Opéra, who caught fire in front of a dress-rehearsal audience in 1862 when her skirt got too close to the gaslights; she died months later from a related infection.

Kelly seems to assume that in this age of reality TV, what lovers of dance really want to know is that ballerinas were glorified concubines in the early days of the art form, that George Balanchine ran his artistically groundbreaking New York City Ballet like a sexually abusive despot, and that the careers of today’s stars are becoming shorter and more difficult due to age discrimination and increasing levels of competition — more dancers and fewer jobs.

Every art form is full of tragic tales of lives cut short and brilliant artists who go insane or kill themselves or who are not discovered until it is too late. Ballet is no more a haven for sad stories than is music, the visual arts, or theater. Dancers are perhaps even less likely than other artists to have interesting biographies because their careers are so short. An attempt to rise to the top in dance is, in its essence, a doomed endeavor. In dance, longevity is an oxymoron.

Kelly presents a thoroughly researched and well-presented primer on dance history. She traces the evolution of ballet from a pastime for the ruling elite in 15th-century France — the age of Louis XIV (who choreographed and performed in his own ballets) — to a more egalitarian art form after the French Revolution and to a 20th-century profession. Her feminist perspective cuts out all the saccharine excesses presented in other dance-history volumes, but her tendency to go “shocking” adds its own particular slant to an art form that, no matter what happened backstage, has always involved beauty and the highest artistic expression.

The examples of African-American ballerina Misty Copeland, who has struggled because of her race, and Jenifer Ringer, the New York City ballerina (and mother) accused by a New York Times dance critic of eating “one sugar plum too many,” shed no light on the art form. They underscore the challenges that all performing artists face, which is nothing new.